Get Rich Quick: The Cultural Logic of the Instant Fortune

Introduction

The “Get Rich Quick” (GRQ) scheme is often dismissed as a peripheral pathology of the market—a collection of scams preying on the desperate or the gullible. However, to view GRQ merely through the lens of fraud is to miss its deeper significance. In reality, the pursuit of the instant fortune functions as a sophisticated cultural operator and a structural artifact of modern economic life. It is not an aberration of the system, but a concentrated expression of its underlying logic. More precisely, GRQ is a rational, albeit destructive, response to the collapse of the post-war social contract—the once-reliable promise that steady labor would yield a home, a pension, and a rising standard of living. With that compact broken by decades of wage stagnation, financialization, and the hollowing out of institutional safety nets, the speculative shortcut becomes less a mark of gullibility than the shadow cast by the modern economic order itself.

GRQ narratives emerge at the intersection of technological disruption, financialization, and the erosion of traditional labor-based social contracts. They serve as a mirror to the contemporary economic condition, reflecting a world where wealth is increasingly decoupled from productivity and where the “big win” is seen as the only viable escape from systemic precarity. By examining the mechanics and mythology of these schemes, we can uncover the anxieties and aspirations that define our current era.

The Mechanics of the Phrase

To understand the enduring power of the “Get Rich Quick” (GRQ) motif, one must look beyond the literal promise and into the rhetorical architecture of the phrase itself. It operates across three distinct layers that make it both a potent memetic virus and a structural necessity in the modern economy. First, the phrase offers the promise of asymmetry. It proposes a world where the traditional ratio of input to output—the grueling logic of hourly wages and incremental savings—is suspended. By promising high returns for minimal effort, it taps into a fundamental human desire for leverage. In a financialized world where capital gains consistently outpace labor income, the GRQ phrase offers the layperson a simulated version of the arbitrage and high-frequency gains enjoyed by the financial elite. It is the democratization of the “shortcut.” Second, GRQ functions as a psychological pressure valve during periods of economic stagnation. When the traditional path of “work hard and succeed” appears broken or inaccessible, the prospect of the instant fortune provides a necessary fantasy of escape. It transmutes systemic frustration into individual hope. By focusing on the possibility of a sudden windfall, the individual can temporarily bypass the crushing reality of wage stagnation and rising costs of living. It is not just a scam; it is a coping mechanism for a world where the middle ground is disappearing. Third, the phrase serves as a marketing primitive for various hype cycles. Whether it is the gold rushes of the 19th century, the dot-com bubble, or the contemporary fervor surrounding cryptocurrencies and “side-hustle” culture, the underlying template remains the same. Beneath the surface details of each era lies a memetic skeleton—a four-part recruitment script that dresses itself in whatever the zeitgeist provides: You’re early. Others don’t understand. This time is different. Act now before the window closes. The first move flatters the mark with insider status; the second reframes skepticism from outsiders as proof of the opportunity’s validity; the third inoculates against historical comparison by insisting that old rules no longer apply; and the fourth manufactures urgency, collapsing deliberation into impulse. This script is the linguistic hook that can be adapted to any new technology or market trend—swap “railroad shares” for “dot-com equity” for “altcoins” and the rhetorical chassis is identical. It provides a ready-made framework for “early adopters” to recruit others, creating the network effects necessary for a bubble to expand. In this sense, GRQ is the engine of the hype cycle, providing the narrative fuel that drives speculative manias.

‘Rich’ as a Class Boundary

The word “rich” itself carries a specific weight in the GRQ lexicon, acting as more than a mere descriptor of net worth. It functions as a linguistic marker of class disparity and social distance. To speak of “getting rich” is to admit, implicitly, that one is currently outside a gated enclave. Unlike “wealthy,” which often implies a stable, multi-generational state of being, “rich” is frequently used to describe a sudden transition or a visible accumulation of resources. It is a term of the outsider looking in. This linguistic choice encodes a profound admission of social immobility. In a truly meritocratic system, the transition from one economic tier to another would be seen as a gradual, predictable outcome of labor and time. However, the fixation on “getting rich” suggests that such a transition is now viewed as a discrete, almost miraculous event. The phrase acknowledges that the gap between the working class and the affluent has become so wide that it can no longer be bridged by incremental steps; it requires a leap. Furthermore, within the current economic framework, these upward leaps are often viewed with a mixture of envy and suspicion. Because the “quick” aspect of GRQ bypasses the traditional moral narrative of “earning” one’s place through decades of toil, the sudden acquisition of wealth is frequently treated as a transgression or a systemic anomaly. The “nouveau riche” are often mocked not just for their taste, but for the perceived illegitimacy of their speed. By aiming to “get rich quick,” the individual is essentially attempting to hack the social hierarchy, an act that the system simultaneously encourages through its speculative structures and punishes through its social codes.

‘Quick’ as a Euphemism for Luck

The “quick” in Get Rich Quick is perhaps the most deceptive element of the triad. While it ostensibly refers to time—the compression of years of labor into weeks or months—it actually serves as a rhetorical sleight of hand that substitutes luck for time. In the standard economic equation, wealth is a function of labor, capital, and time. To remove the time variable while keeping the labor and capital inputs low, one must introduce a hidden variable: extreme variance, or luck. This substitution is embedded in our language. The word “fortune” serves a dual purpose, referring both to a large sum of money and to the blind forces of fate. This is not a linguistic coincidence. Historically, the acquisition of a “fortune” was understood to be as much a matter of “good fortune” (luck) as it was of industry. The etymology betrays the whole game in a single phrase: to “get rich quick” is, at bottom, to acquire a fortune by fortune—to obtain wealth by luck, the two meanings of the word collapsing into a tautology that the GRQ narrative must constantly obscure. By focusing on the “quickness” of the gain, the GRQ narrative effectively offloads the immense cost of wealth creation onto the dimension of luck. It suggests that the time usually required to build value can be bypassed if one simply finds the right “opportunity”—a euphemism for a high-variance event where the odds are heavily stacked against the participant. In this framework, “quick” is not a measure of efficiency, but a measure of risk. It masks the reality that for every individual who gets rich “quick,” thousands of others must lose “quick” to provide the necessary liquidity for that outlier event. This is the zero-sum logic that the GRQ narrative must suppress: in speculative markets, wealth is not created but transferred—the winner’s fortune is extracted directly from the pockets of the losers who serve, unwittingly, as “exit liquidity” in what amounts to a massive, unregulated poker game. The focus on speed allows the promoter to ignore the mathematical impossibility of the promise being scaled. It transforms a statistical anomaly into a repeatable strategy, hiding the graveyard of failed attempts behind the blinding speed of the winner’s ascent.

The Social Opiate and Systemic Infantilization

Beyond its role as a marketing hook or a psychological pressure valve, the Get Rich Quick (GRQ) myth functions as a sophisticated form of social control—a psychological analgesic that numbs the pain of systemic inequality. By framing economic advancement as a matter of “cracking the code” or stumbling upon the right “alpha,” the system encourages a form of magical thinking that infantilizes the citizenry. Instead of engaging with the complex, often dry realities of economic policy, labor rights, or tax structures, the individual is redirected toward a gamified pursuit of the windfall. This shift from systemic engagement to speculative participation creates a profound political inertia. When the primary hope for economic security is shifted from collective bargaining or social safety nets to the individual lottery of the market, the motivation for structural reform evaporates. The GRQ narrative suggests that the system doesn’t need to be fixed; it just needs to be won. This perspective transforms the citizen into a gambler, perpetually waiting for their turn at the table rather than questioning why the table is tilted in the first place. The transformation here is not merely one of attention but of identity. The GRQ apparatus does not simply distract the citizen from reform; it fundamentally reconstitutes the citizen as a different kind of subject—a market participant, a gambler, a player of odds. This is a categorical shift, not a gradual one. A citizen has standing to make demands of institutions; a gambler has only a stake in the next hand. A citizen organizes; a gambler refreshes a portfolio. The political vocabulary of rights, solidarity, and collective bargaining is quietly replaced by the market vocabulary of risk, timing, and “alpha.” Once this substitution is complete, structural critique becomes almost literally unthinkable—not because the individual lacks intelligence, but because the cognitive frame through which they interpret their own economic life no longer contains the category of “systemic failure.” There is only the next bet, the next opportunity, the next cycle. And here lies the deepest political utility of the luck-based narrative that undergirds the entire GRQ mythology: luck is politically inert—luck doesn’t have a lobby. If wealth is understood as the product of policy, regulation, and institutional design, then the losers of the economic game have a clear target for collective action. But if wealth is understood as the product of fortune, timing, and individual daring, there is no one to petition and nothing to reform. You cannot march on probability. You cannot unionize against chance. The luck framework scatters political energy into a million isolated wagers, each one a private transaction between the individual and fate, rather than a public grievance between the citizen and the state.

Furthermore, the GRQ framework establishes a devastating self-blame loop that reinforces this identity collapse. Because these schemes are marketed as accessible to anyone with the “right mindset” or “enough hustle,” failure is internalized as a personal deficiency rather than a statistical certainty. When the “quick” fortune fails to materialize, the individual—now fully inhabiting the role of the gambler rather than the citizen—does not look at the predatory nature of the scheme or the structural barriers to wealth; they look at their own lack of discipline or vision. This internalization of failure acts as a firewall against structural critique, ensuring that the frustration generated by economic hardship is directed inward at the self, rather than outward at the institutions that perpetuate it. The gambler who loses does not blame the house; the gambler blames their own read of the table. In this sense, the GRQ myth is the ultimate tool of “stupification,” replacing class consciousness with a desperate, isolated pursuit of the miracle. To be clear, the indictment here is not of the individuals caught in this cycle—it is not that people are inherently foolish or lack the capacity for critical thought. It is that the system cultivates a cognitive environment where magical thinking feels like the only available strategy, systematically replacing the tools of structural analysis with the vocabulary of luck and hustle until the speculative bet appears more rational than the collective demand. Yet when the self-blame loop does eventually crack—when enough participants recognize that the game is rigged and that their failure was never truly personal—the result is not necessarily the structural critique one might hope for. Instead, what frequently emerges is a condition best described as financial nihilism: a widespread, cynical awareness that the system is a casino, paired not with a demand for reform but with a defiant resolve to gamble even harder—hence the “YOLO” trades, the meme coins, the performative recklessness of a generation that has replaced the earnest hustle narrative with an ironic, eyes-open wager against the void. This is perhaps the GRQ dynamic’s most insidious final form, because it captures even disillusionment within the logic of the game; the house does not need its players to believe the table is fair—it only needs them to keep playing.

The Colosseum Effect

The “Colosseum Effect” describes the phenomenon where the public spectacle of a few individuals achieving massive, life-altering wealth serves to validate the entire economic structure for the masses who remain in precarity. Much like the gladiatorial games of ancient Rome, which provided a violent but engrossing distraction for the Roman populace, the modern spectacle of the “big win” creates a shared cultural ritual of hope. The most pervasive example of this effect is the state-run lottery. Lotteries are, mathematically speaking, regressive taxation disguised as hope—extracting billions in revenue from those least able to afford it while wrapping the extraction in the language of dreams and possibility. However, they are marketed not as a tax, but as a dream. The televised drawing of numbers and the public celebration of winners function as a secular liturgy—and it is crucial to understand that the broadcast is not merely a promotional tool for the lottery; the broadcast is the product. The spectacle of the drawing, the slow revelation of numbers, the cutaway to the ecstatic winner—this is the mechanism by which the emotional investment is manufactured and sustained. Without the spectacle, there is no shared emotional investment, and without that shared investment, the entire apparatus of voluntary, regressive extraction collapses. The lottery ticket is just the entry fee; what is actually being sold is participation in a collective ritual of anticipation and vicarious triumph. By showcasing a regular person—a “janitor from Ohio” or a “teacher from Florida”—who has suddenly ascended to the ranks of the elite, the system provides a visible, if statistically impossible, proof of concept. This spectacle serves as a powerful social glue. It reinforces the belief that the system is “fair” because, in theory, anyone could be the next winner. The ritualized hope generated by the lottery prevents the total collapse of belief in the possibility of upward mobility. It transforms the extraction of wealth from the precarious into a voluntary participation in a collective fantasy. The Colosseum Effect ensures that even as the material conditions for the majority stagnate, the psychological investment in the system remains intact, fueled by the flickering image of the one who made it out.

But the analogy to Rome should not be taken as merely illustrative—it carries a diagnostic weight. A society that must rely on spectacle to maintain social cohesion and to keep its precarious classes invested in the legitimacy of the order is, by any honest reckoning, a society in decline. The Roman games intensified not during the Republic’s vigor but during the Empire’s long erosion, when the mechanisms of genuine civic participation had already been hollowed out. The modern proliferation of lottery spectacles, reality-show windfalls, and gamified investment platforms follows the same trajectory: the spectacle expands precisely as the substance contracts. When the primary instrument for sustaining belief in upward mobility is not policy or opportunity but a televised drawing of numbered balls, we are witnessing not a quirk of entertainment culture but a sign of a decadent society—one that has substituted the ritual of hope for the reality of it.

Conclusion: The Cultural Technology of Aspiration

In the final analysis, the “Get Rich Quick” narrative is the smoke, not the fire—a lagging indicator of systemic failure rather than the failure itself. Its proliferation signals that the traditional mechanisms of upward mobility have already broken down; the scheme arrives after the damage is done, offering a counterfeit map to an exit that the economy has already sealed. Understood this way, GRQ is far more than a collection of opportunistic scams; it is a sophisticated cultural technology essential to the maintenance of the modern economic order. By transmuting the harsh realities of structural inequality into a series of individual aspirations, it effectively neutralizes the potential for collective dissent. The promise of the instant fortune functions as a psychological bridge over an ever-widening chasm of class disparity, offering a mirage of mobility where the actual paths have been eroded. In the final analysis, the “Get Rich Quick” narrative is the smoke, not the fire—a lagging indicator of systemic failure rather than the failure itself. Its proliferation signals that the traditional mechanisms of upward mobility have already broken down; the scheme arrives after the damage is done, offering a counterfeit map to an exit that the economy has already sealed. Understood this way, GRQ is far more than a collection of opportunistic scams; it is a sophisticated cultural technology essential to the maintenance of the modern economic order. By transmuting the harsh realities of structural inequality into a series of individual aspirations, it effectively neutralizes the potential for collective dissent. The promise of the instant fortune functions as a psychological bridge over an ever-widening chasm of class disparity, offering a mirage of mobility where the actual paths have been eroded and where debt—mortgages, student loans, consumer credit—serves as the anchor that binds the disillusioned to the very cycle of labor-and-speculation they can now see through but cannot exit. This technology operates through a dual mechanism of hope and shame. For those still in the pursuit, it provides a narrative of agency and potential, framing the systemic lottery as a meritocratic “hustle.” For those who inevitably fail, it provides a framework of personal inadequacy, ensuring that the frustration of economic precarity is internalized as a private failure rather than a public grievance. In both cases, the result is the same: the status quo remains unchallenged. By keeping the gaze of the precarious fixed on the flickering light of the “big win,” the GRQ myth ensures that the structural foundations of the “table” are never questioned, protecting the interests of the few by selling a statistically impossible dream to the many. And it is not merely statistically impossible but structurally so: the system requires the failure of the majority to function, because the winner’s windfall is extracted from the losses of the many who provided the liquidity, the buy-in, and the belief. If everyone could exit the game as a winner, there would be no game at all—the dream scales only so long as most dreamers lose.

Comic Book Generation Task

Generated Script

Full Script

The Instant Fortune

In a decaying metropolis where the post-war social contract has evaporated, a weary janitor named Elias witnesses the predatory mechanics of “Get Rich Quick” schemes. The comic explores how the promise of a sudden windfall serves as a psychological anesthetic, transforming citizens into gamblers and neutralizing political dissent through the “Colosseum Effect” of the modern lottery.

Characters

- Elias: A middle-aged man with tired, deep-set eyes and a slight slouch. He wears a faded, grease-stained janitor’s uniform. His face is expressive of weary cynicism. Observant, disillusioned, but intellectually sharp. He sees the ‘gears’ of the system that others ignore. (Often seen with a mop or a trash bag; his silhouette is heavy and grounded compared to the flickering neon around him.)

- The Promoter: A slick figure in a sharp, iridescent suit that seems to change color (shifting between oil-slick greens and predatory purples). Predatory, persuasive, and entirely hollow. He speaks in the ‘4-part script’ of the hype cycle. (His face is often partially obscured by a digital glitch effect or a glowing holographic mask that displays a permanent, artificial smile. He radiates high-energy, artificial charisma.)

Script

Page 1

Row 1

- Panel 1: A close-up of a vintage, peeling billboard from the 1950s. It shows a smiling family in front of a suburban home. The text reads: “Hard Work = A Bright Future.”

- Panel 2: Wide shot. Elias is standing in front of the billboard, dwarfed by it. He is emptying a trash can. The background is a grey, rain-slicked street.

- Caption: The promise was simple: steady labor for a steady life. A home. A pension. A rising tide. Row 2

- Panel 1: Elias walks past a row of shuttered storefronts. The windows are boarded up with “For Lease” signs that look decades old.

- Panel 2: A high-angle shot of a crowded subway platform. Everyone looks exhausted, hunched over, bathed in the sickly yellow light of the station.

- Caption: But the contract was torn up decades ago. Stagnation set in. The safety nets were sold for parts. Row 3

- Panel 1: Elias looks up at a massive neon sign flickering above the slums. It’s an ad for a crypto-trading app: “DON’T JUST WORK. WIN.”

- Panel 2: Elias’s face in profile, half-hidden in deep shadow, half-lit by the aggressive cyan neon of the sign.

- Caption: When the middle ground disappears, the shortcut isn’t a scam. It’s the only exit left.

Page 2

Row 1

- Caption: When the middle ground disappears, the shortcut isn’t a scam. It’s the only exit left.

- Panel 1: A young man (The Mark) sits on a bus bench, looking at a mounting pile of bills. The Promoter leans into the frame, his iridescent suit shimmering.

- Panel 2: Close-up of The Promoter’s holographic mask. A digital mouth moves.

- The Promoter: “You’re early, kid. Most people are still sleeping on this.” Row 2

- Panel 1: The Promoter puts a hand on the Mark’s shoulder. In the background, Elias is mopping the sidewalk, watching them.

- The Promoter: “Others don’t understand. They’ll call it a bubble because they’re scared of the future.”

- Panel 2: The Promoter gestures to a glowing tablet showing a vertical green line on a chart.

- The Promoter: “But this time is different. The old rules? They’re dead.” Row 3

- Panel 1: The Promoter leans in close to the Mark’s face. The glitch effect on his suit intensifies.

- The Promoter: “Act now. Before the window closes. Before you’re left behind with the rest of the ghosts.”

- Panel 2: The Mark hands over a credit card. Elias watches from the shadows, his face a mask of grim recognition.

- Caption: It’s a memetic virus. A four-part script dressed in the zeitgeist of the week.

Page 3

Row 1

- Caption: It’s a memetic virus. A four-part script dressed in the zeitgeist of the week.

- Panel 1: A massive, seamless chrome wall rises out of the slums, disappearing into the clouds. At the top, golden lights of a floating city are visible.

- Panel 2: Elias stands at the base of the wall, looking up. He looks like an ant.

- Caption: We don’t say ‘wealthy’ anymore. We say ‘rich.’ It’s a marker of distance. An admission that we’re on the outside looking in. Row 2

- Panel 1: A sleek, silent hover-car glides over the wall. Below, people in the mud watch it with a mix of hunger and hatred.

- Panel 2: Close-up of Elias’s hand gripping his mop handle.

- Caption: In a meritocracy, you climb. In this world, you have to hack the hierarchy. You have to leap. Row 3

- Panel 1: A holographic news feed shows a “lottery winner” in a gaudy, oversized mansion, looking uncomfortable.

- Panel 2: Elias turns away from the wall, heading back into the dark alleys.

- Caption: The system punishes the speed it encourages. The ‘quick’ gain is a transgression. A glitch in the social code.

Page 4

Row 1

- Caption: The system punishes the speed it encourages. The ‘quick’ gain is a transgression. A glitch in the social code.

- Panel 1: Elias walks down a street where the pavement has turned into a giant roulette wheel. People are throwing “Time” (represented by glowing pocket watches) onto the numbers.

- Panel 2: A man loses his watch; it shatters. He looks aged instantly.

- Caption: ‘Quick’ is just a euphemism for luck. To get a fortune… you need good fortune. Row 2

- Panel 1: The Promoter is the dealer at a high-stakes table. He’s dealing cards that are blank until they hit the table.

- The Promoter: “High variance, high reward! Who needs a forty-year career when you have forty seconds?”

- Panel 2: Elias stands behind the players, seeing the “Exit Liquidity” written on their backs in invisible neon ink. Row 3

- Panel 1: A winner at the table rakes in a pile of glowing watches. Around him, dozens of people collapse in the shadows, their “Time” drained.

- Panel 2: Close-up of Elias’s eyes reflecting the flashing “JACKPOT” sign.

- Caption: For one to get rich quick, thousands must lose quick. The winner’s fortune is just the losers’ life-blood, transferred.

Page 5

Row 1

- Caption: For one to get rich quick, thousands must lose quick. The winner’s fortune is just the losers’ life-blood, transferred.

- Panel 1: A group of workers who should be protesting a “Factory Closing” sign are instead huddled around a single smartphone, cheering a price chart.

- Panel 2: Their faces are featureless, replaced by the glowing UI of a trading app.

- Caption: The citizen is dead. Long live the gambler. Row 2

- Panel 1: Elias mops around a man who is frantically refreshing a portfolio while a bridge crumbles in the background.

- Panel 2: Elias tries to speak to him, but the man doesn’t look up.

- Elias: “The water’s rising, friend.”

- Gambler: “Not now… I’m waiting for the bounce. I’ve got alpha.” Row 3

- Panel 1: A woman sits on the ground, head in her hands, her screen showing “LIQUIDATED.”

- Panel 2: She isn’t looking at the Promoter or the system. She’s looking at her own hands.

- Caption: If you lose, it’s your fault. Your lack of hustle. Your bad timing. Luck has no lobby. You can’t unionize against chance.

Page 6

Row 1

- Caption: If you lose, it’s your fault. Your lack of hustle. Your bad timing. Luck has no lobby. You can’t unionize against chance.

- Panel 1: A giant holographic screen towers over the city square. It shows a golden tumbler filled with numbered balls. Thousands of people watch in total silence.

- Panel 2: Elias stands at the edge of the crowd, a small, dark figure against the overwhelming light.

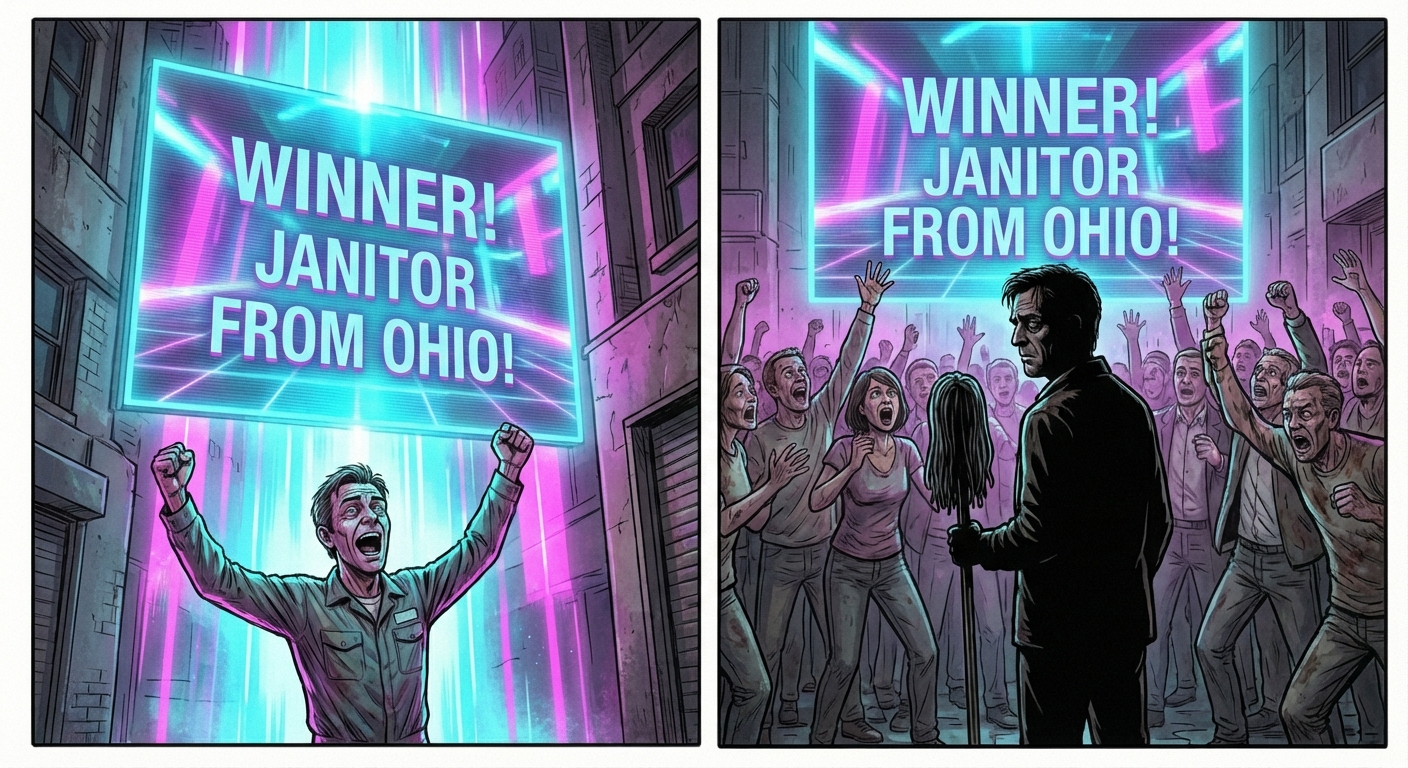

- Caption: The Colosseum Effect. The big win validates the cage. Row 2

- Panel 1: The screen explodes in light. A number is revealed. A “Janitor from Ohio” (looking much like a younger Elias) is shown screaming in joy.

- Panel 2: The crowd erupts in a terrifying, desperate cheer.

- Caption: The broadcast is the product. It’s the ritual of hope that keeps the extraction voluntary. Row 3

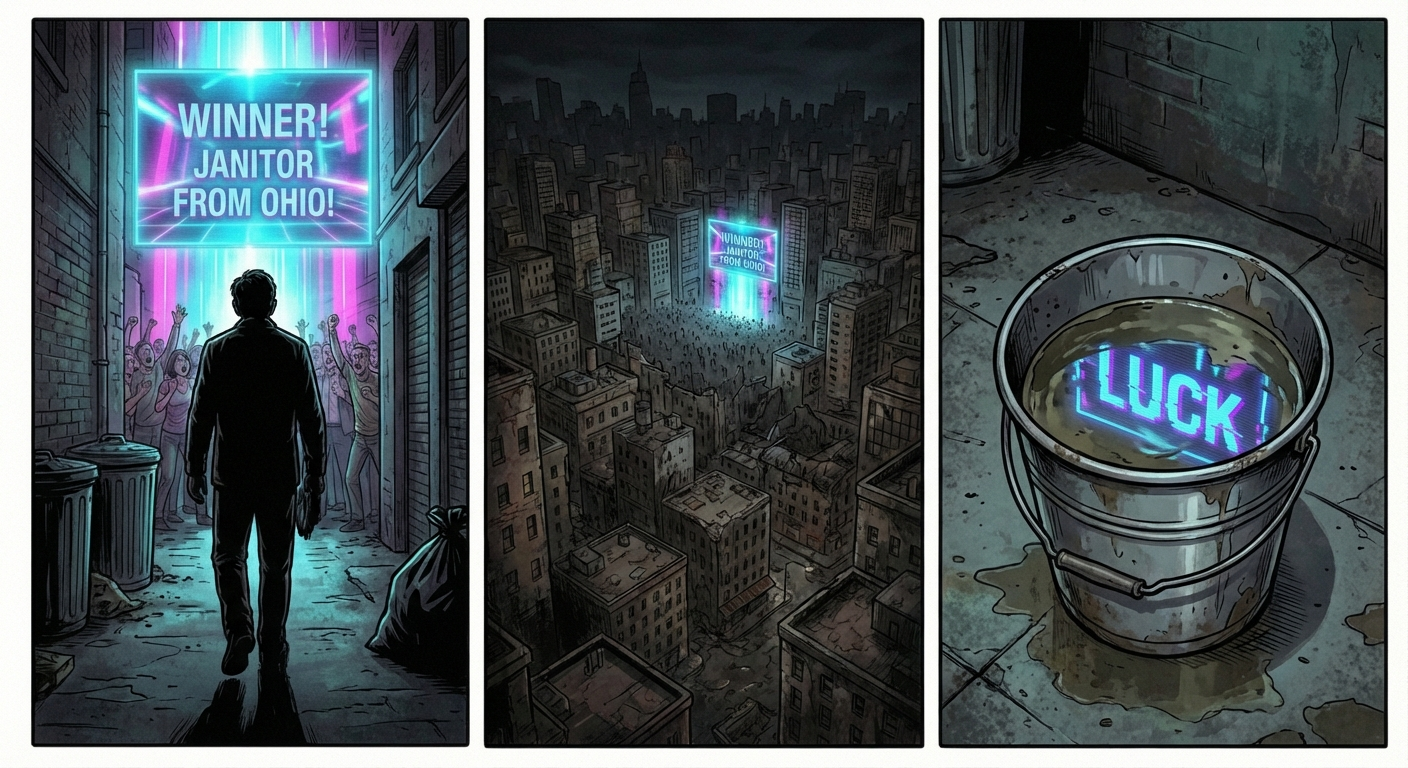

- Panel 1: Elias turns his back on the celebration, walking down a dark, quiet alleyway. The neon glow fades behind him.

- Panel 2: A wide shot of the city. The bright, fake light of the lottery screen is a tiny dot in a vast, crumbling darkness.

- Caption: A society that relies on spectacle to maintain belief is a society in decline. The smoke is everywhere. But the fire… the fire went out a long time ago.

- Panel 3: Elias’s mop bucket sits alone in the foreground. In the reflection of the dirty water, the word “LUCK” flickers in neon.

Auto-Fix Mode

Auto-applying: proceeding directly to visual generation.

Character: Elias

A middle-aged man with tired, deep-set eyes and a slight slouch. He wears a faded, grease-stained janitor’s uniform. His face is expressive of weary cynicism. Observant, disillusioned, but intellectually sharp. He sees the ‘gears’ of the system that others ignore.

Character: The Promoter

A slick figure in a sharp, iridescent suit that seems to change color (shifting between oil-slick greens and predatory purples). Predatory, persuasive, and entirely hollow. He speaks in the ‘4-part script’ of the hype cycle.

Narrative Generation Task

Overview

Narrative Generation

Subject: The Cultural Logic of the Instant Fortune

Configuration

- Target Word Count: 2500

- Structure: 3 acts, ~2 scenes per act

- Writing Style: literary thriller

- Point of View: third person limited

- Tone: dramatic and reflective

- Detailed Descriptions: ✓

- Include Dialogue: ✓

- Internal Thoughts: ✓

Started: 2026-02-20 20:38:23

Progress

Phase 1: Narrative Analysis

Running base narrative reasoning analysis…

Cover Image

Prompt:

High-Level Outline

The Cultural Logic of the Instant Fortune

Premise: A former investigative journalist discovers a massive digital fortune linked to a defunct shadow-banking firm, forcing him to navigate the predatory world of the ultra-wealthy and the moral cost of unearned wealth.

Estimated Word Count: 2496

Characters

Elias Thorne

Role: protagonist

Description: 38 years old, gaunt with deep-set eyes that suggest chronic insomnia. A former investigative journalist who specialized in white-collar crime before a burnout led him to a dead-end data entry job. He wears thrift-store suits that hang loosely on his frame.

Traits: Analytical, paranoid, and deeply cynical. He is motivated by a desire for security but is haunted by the ‘logic’ of the money—the belief that such wealth cannot exist without a corresponding debt elsewhere.

Julian Vane

Role: antagonist

Description: Ageless, impeccably groomed, wearing bespoke charcoal wool. He speaks in a soft, rhythmic cadence. He is a ‘wealth transition specialist’ for the ultra-high-net-worth.

Traits: Predatory, philosophical, and cold. He views wealth as a biological apex and seeks to mold Elias into a ‘pure’ vessel for the capital, stripping away his humanity in the process.

Sarah Thorne

Role: supporting

Description: Elias’s younger sister. A social worker with calloused hands and a weary but kind face. She represents the ‘old world’ of labor and tangible value.

Traits: Empathetic, grounded, and suspicious of shortcuts. She wants Elias to be safe but recognizes the rot the money brings.

Settings

concrete_hive

Description: A cramped, fourth-floor walk-up in a neighborhood defined by gray skies and the hum of a nearby highway. The air smells of stale coffee and old paper.

Atmosphere: The Logic of Scarcity; oppressive and mundane.

Significance: Represents Elias’s starting point and the reality of the working class.

glass_spire

Description: A minimalist, high-tech apartment on the 80th floor. Floor-to-ceiling windows make the city look like a circuit board.

Atmosphere: The Logic of the Void; silent, sterile, and terrifyingly exposed.

Significance: Represents the isolation and moral vacuum of extreme wealth.

the_vault

Description: An underground, windowless lounge built into a former bank vault. Dark wood, velvet, and the muffled sound of high-stakes transactions.

Atmosphere: The Logic of the Secret; heavy, exclusive, and predatory.

Significance: The site of the final confrontation where the true nature of the fortune is revealed.

Act Structure

Act 1: The Rupture

Purpose: To establish the transition from desperation to sudden, unearned power and the psychological shock that follows.

Estimated Scenes: 2

Key Developments:

- Elias discovers the fortune

- He meets Julian Vane

- He realizes his old life is instantly obsolete

Act 2: The Acceleration

Purpose: To build tension through the ‘thriller’ elements of surveillance and the moral erosion of the protagonist.

Estimated Scenes: 2

Key Developments:

- Elias moves into the Spire

- He attempts to ‘buy’ his sister’s happiness

- He discovers the fortune is tied to a violent disappearance

Act 3: The Reckoning

Purpose: To bring the ‘Cultural Logic’ to its inevitable, dark conclusion where the fortune demands its payment.

Estimated Scenes: 2

Key Developments:

- A confrontation in The Vault

- Elias must choose between the money and his identity

- The final ‘cost’ is revealed

Status: ✅ Pass 1 Complete

Outline

The Cultural Logic of the Instant Fortune

Premise: A former investigative journalist discovers a massive digital fortune linked to a defunct shadow-banking firm, forcing him to navigate the predatory world of the ultra-wealthy and the moral cost of unearned wealth.

Estimated Word Count: 2496

Total Scenes: 6

Detailed Scene Breakdown

Act 1: The Rupture

Purpose: To establish the transition from desperation to sudden, unearned power and the psychological shock that follows.

Scene 1: The Ghost in the Ledger

- Setting: concrete_hive

- Characters: Elias Thorne, Sarah Thorne

- Purpose: Elias discovers the fortune.

- Emotional Arc: Elias moves from the soul-crushing ‘Logic of Scarcity’ and brittle pride to a state of ‘rupture’ where his reality is shattered by the discovery of $412 million.

- Est. Words: 1200

Key Events: { “context” : “Elias is performing digital salvage in the Concrete Hive, struggling with poverty.”, “interaction” : “Sarah visits, bringing food and highlighting the strain of Elias’s pride and their differing worlds.”, “discovery” : “Elias bypasses security on a ghost account from Aethelgard Holdings.”, “climax” : “Elias finds a digital wallet containing $412 million, causing a profound psychological shock.” }

Scene 2: The Onboarding

- Setting: concrete_hive

- Characters: Elias Thorne, Julian Vane

- Purpose: Elias meets Julian Vane; he realizes his old life is instantly obsolete.

- Emotional Arc: Elias transitions from the shock of his discovery to the ‘Logic of the Instant’ as Julian Vane convinces him that his past is a ‘vestigial organ’.

- Est. Words: 1200

Key Events: { “arrival” : “Julian Vane arrives at Elias’s apartment, appearing like a ‘glitch in the matrix’.”, “proposition” : “Vane explains the money ‘selected’ Elias and presents him with a black titanium card.”, “philosophical_shift” : “Vane mocks Elias’s old life and argues that possessing such capital requires shedding human ‘friction’.”, “departure” : “Elias leaves his apartment and his history behind, entering a waiting black sedan.” }

Act 2: The Acceleration

Purpose: To build tension through the ‘thriller’ elements of surveillance and the moral erosion of the protagonist.

Scene 1: The Transparency of Gold

- Setting: glass_spire

- Characters: Elias Thorne, Sarah Thorne, Julian Vane

- Purpose: Elias moves into the Spire; He attempts to “buy” his sister’s happiness; The realization of constant surveillance.

- Emotional Arc: Elias transitions from a performative sense of success to defensive anger and finally to a realization of his own entrapment as a specimen. Sarah feels alienated and morally repulsed.

- Est. Words: 1200

Key Events: { “arrival” : “Elias moves into the high-tech Spire apartment and attempts to provide Sarah with a deed and trust fund.”, “conflict” : “Sarah refuses the money, describing it as having a ‘moral stench,’ leading to a defensive argument from Elias.”, “realization” : “Elias discovers he cannot control the lights, realizing the apartment’s ‘anticipatory service’ is actually surveillance.”, “climax” : “After Sarah leaves in tears, Julian Vane’s voice confirms Elias is now a specimen under observation.” }

Scene 2: The Ghost in the Ledger

- Setting: glass_spire

- Characters: Elias Thorne, Julian Vane

- Purpose: Elias discovers the fortune is tied to a violent disappearance; The moral erosion of his investigative instincts.

- Emotional Arc: Elias moves from a spark of his old investigative integrity to horror, and finally to a calculated, soul-eroding decision to prioritize wealth over truth.

- Est. Words: 1200

Key Events: { “investigation” : “Elias uses his old journalistic skills to bypass the wealth management interface and trace the source of his money.”, “discovery” : “He finds that his fortune belonged to Arthur Penhaligon, a whistleblower who was ‘liquidated’ and had his assets pooled.”, “confrontation” : “Julian Vane appears and explains the ‘Cultural Logic’ that an instant fortune requires someone else’s sudden absence.”, “decision” : “Given the choice to delete the money or keep it, Elias chooses to hide the evidence, completing his moral acceleration.” }

Act 3: The Reckoning

Purpose: To bring the ‘Cultural Logic’ to its inevitable, dark conclusion where the fortune demands its payment.

Scene 1: The Architecture of the Debt

- Setting: the_vault

- Characters: Elias Thorne, Julian Vane

- Purpose: Confrontation in The Vault; Revelation of the fortune’s true nature.

- Emotional Arc: Elias shifts from a state of confrontational demand for truth to a realization of metaphysical horror; Vane remains unnervingly calm and clinical.

- Est. Words: 1200

Key Events: { “confrontation” : “Elias confronts Vane with evidence of the previous owner’s disappearance.”, “revelation_of_logic” : “Vane explains the ‘Cultural Logic’—the fortune is the distilled essence of systemic failure and diverted resources.”, “fate_of_predecessor” : “Vane reveals the previous owner was ‘liquidated’ for attempting philanthropy.”, “the_selection” : “Vane explains that Elias was chosen for his cynicism to be a hollow vessel for the debt.” }

Scene 2: The Final Liquidation

- Setting: the_vault

- Characters: Elias Thorne, Julian Vane, Sarah Thorne

- Purpose: Elias chooses between the money and his identity; The final ‘cost’ is revealed.

- Emotional Arc: A peak of tension and agonizing clarity; Elias moves from desperation to a hollow, self-sacrificing resolution, ending in total erasure.

- Est. Words: 1500

Key Events: { “the_contract” : “Vane offers Elias a role as a ‘Ghost Director’ in exchange for financial stability.”, “the_threat” : “Vane reveals that Sarah is facing ruin because of Elias’s previous attempts to help her.”, “the_choice” : “Elias signs the contract to save Sarah, effectively severing his ties to the tangible world.”, “the_erasure” : “Vane reveals the final cost: Sarah can never know Elias saved her, and his identity is absorbed by the market.” }

Status: ✅ Complete

Setting: concrete_hive

Prompt:

Setting: glass_spire

Prompt:

Setting: the_vault

Prompt:

Character: Elias Thorne

Prompt:

Character: Julian Vane

Prompt:

Character: Sarah Thorne

Prompt:

## The Ghost in the Ledger

Act 1, Scene 1

Setting: concrete_hive

Characters: Elias Thorne, Sarah Thorne

The air in the Concrete Hive tasted of ozone and the metallic rot of a dying cooling fan. It was a brutalist apartment on the twenty-second floor, part of a complex designed as a mid-century utopian collective that had long since soured into a vertical graveyard for the underclassed. Elias Thorne sat at a desk fashioned from a salvaged fire door, his face bathed in the flickering, sickly blue luminescence of three mismatched monitors.

He was a digital scavenger, a forensic archaeologist of the bankrupt. He spent his days picking through the encrypted detritus of failed corporations, hunting for “lost” assets—unclaimed dividends, forgotten server space, or proprietary code that could be fenced to the highest bidder for a few hundred dollars. It was a far cry from the front-page bylines he’d once commanded at the Chronicle, before the lawsuits and the “restructuring” had stripped him of his career, his reputation, and his dignity.

A sharp, rhythmic knocking at the door fractured his concentration. Elias didn’t move. He knew the cadence. It was the knock of someone who possessed a key but still retained the politeness to ask for entry.

“Elias? I’m coming in.”

Sarah Thorne entered, carrying a plastic bag that leaked the scent of ginger and cheap soy sauce. She was three years younger than Elias, but in the harsh, unforgiving light of the Hive, she looked like the elder. Her professional attire—a sharp charcoal blazer and tailored slacks—was a jarring intrusion into his world of tangled cables, stained coffee mugs, and dust.

“You haven’t answered your phone in two days,” she said, clearing a space on the fire door to set down the Thai takeout.

“I’ve been close to something,” Elias muttered. His eyes never left the screen, his voice raspy from disuse.

“You’re always close to something, El. Usually, it’s a nervous breakdown.” She reached out, her hand hovering over his shoulder for a heartbeat before she pulled it back, sensing the invisible wall he’d built around himself. “I brought Pad See Ew. Eat. Please.”

Elias finally looked at her. The “Logic of Scarcity,” as he called it, was etched into the lines around his eyes. He lived in a world where every calorie was a calculation, every kilowatt-hour a debt to be managed. His pride was a brittle thing, a thin glass barrier held up by the stubborn refusal to admit he was drowning.

“I can pay you back for the last three weeks by Friday,” he said, his jaw tightening until it ached.

Sarah sighed, a sound of profound, weary exhaustion. “I don’t want your money, Elias. I want you to come back to the world. There’s a research position open at the firm. It’s not investigative journalism, but it’s steady. It’s health insurance. It’s a life that doesn’t involve living in a concrete box.”

“I’m not a clerk, Sarah.”

“No, you’re a ghost,” she snapped, her patience finally fraying. “You’re haunting your own life. Look at this place. You’re digging through the trash of people who wouldn’t spit on you if you were on fire.”

She gestured toward the monitors, where a complex directory of files from Aethelgard Holdings was splayed open like a vivisected corpse. Aethelgard had been a shadow-banking firm that vanished during the 2022 crash, leaving behind a trail of ruined pensions and a labyrinth of offshore shells.

“Aethelgard is different,” Elias said, his voice dropping to a low, feverish whisper. “They didn’t just go bust. They erased themselves. There’s a ghost account, Sarah. A ledger entry that doesn’t resolve. It’s been driving me crazy for a month.”

Sarah looked at the screen, then back at her brother. Her expression softened from anger to pity, which felt like a physical blow to his chest. “Eat the food, Elias. I’ll see you Sunday. Mom’s asking about you.”

She left the key on the table and walked out. The heavy steel door thudded shut, the sound echoing in the small, cramped space like a gavel. Elias stared at the Pad See Ew. The steam rising from the container felt like a luxury he hadn’t earned. He pushed it aside and turned back to the screen.

The Logic of Scarcity dictated that he should stop. He should sleep. He should take the job Sarah offered and crawl back into the light of the mundane. But there was a different logic at work now—the logic of the hunt.

He returned to the Aethelgard directory. He had been running a brute-force decryption on a specific sub-folder for seventy-two hours. It was labeled Project Lethe. In Greek mythology, Lethe was the river of forgetfulness.

The screen flickered. A command prompt blinked with cold finality: DECRYPTION COMPLETE. ACCESS GRANTED.

Elias felt a cold prickle of sweat on the back of his neck. He navigated through the decrypted layers. It wasn’t a folder of documents or emails. It was a single, standalone application—a digital wallet interface, ancient by modern tech standards, wrapped in a proprietary encryption layer that had finally buckled under his persistence.

He clicked the executable. A window opened, stark and minimalist. No branding. No logos. Just a hexadecimal address and a balance field.

The cursor blinked for three seconds. Then, the numbers populated.

Elias leaned forward, his breath hitching. He counted the digits. He counted them again, his finger physically touching the dusty glass of the monitor as if he could feel the weight of the numbers.

Balance: $412,000,000.00

The room seemed to tilt. The hum of the cooling fans grew deafening, a roar of white noise that filled his skull. Four hundred and twelve million dollars. It wasn’t just money; it was a statistical impossibility. It was more wealth than every person in the Concrete Hive would earn in their combined lifetimes.

He checked the currency. It wasn’t a defunct crypto-token or a simulated value. It was linked to a series of bearer bonds and liquid assets held in a neutral custodial account in Singapore. It was “dark” money—unclaimed, untaxed, and, according to the ledger, belonging to a shell company whose sole director had died in a plane crash over the Jura Mountains five years ago.

Elias stood up so abruptly his chair clattered to the floor. He backed away from the desk, his heart hammering against his ribs like a trapped bird.

The Logic of Scarcity had been his reality for three years. He knew the price of a bus pass. He knew which grocery store marked down its bread at 9:00 PM. He knew the exact weight of a nickel in his pocket.

This number on the screen was a rupture. It was a tear in the fabric of his universe.

He looked at the Thai food Sarah had brought. It looked pathetic. The plastic container, the cheap wooden chopsticks—they were artifacts of a man who no longer existed.

He walked to the window. Below, the city was a grid of amber lights and crawling traffic. Millions of people were down there, grinding out their lives for the price of a mortgage, a car payment, a meal. He had spent his career writing about the “little guy,” the victims of corporate greed, the systemic rot of the financial world.

Now, he was holding the rot in his hands.

He returned to the screen. The $412 million sat there, silent and glowing. It was a ghost in the ledger, a fortune that had forgotten to be spent.

His hand trembled as he reached for the mouse. He didn’t know how to transfer it yet. He didn’t know who was watching. He didn’t know if this was a gift or a death sentence. But as he looked at the balance, the brittle pride that had sustained him for years began to dissolve, replaced by something much more dangerous: the sudden, terrifying realization that he could do anything.

He could save Sarah. He could burn the people who had ruined him. He could buy the building he was standing in and tear it down with his bare hands.

The “Instant Fortune” wasn’t just wealth. It was a transformation of the soul.

Elias Thorne sat back down. He didn’t eat the food. He watched the cursor blink, a steady, rhythmic heartbeat in the dark. He was no longer a scavenger. He was the most powerful man in the building, and the world didn’t even know he was there yet.

He began to type.

Word Count: 1396

Key Moments:

- The Setting of the Hive: Established Elias’s life of ‘digital salvage’ and the crushing reality of his poverty and fallen status.

- The Sibling Conflict: Sarah’s visit highlighted the tension between Elias’s pride and his actual circumstances, establishing the ‘Logic of Scarcity.’

- The Technical Breakthrough: Elias successfully bypasses the encryption on the Aethelgard Holdings ‘Project Lethe’ file.

- The Rupture: Elias discovers the $412 million balance, experiencing a profound psychological shift from a man defined by lack to a man defined by sudden, overwhelming power.

Character States:

- Elias Thorne: Ends the scene in a state of ‘rupture.’ He is physically trembling and psychologically shocked. His old identity as a struggling journalist is being overwritten by the sheer gravity of the fortune. He is hyper-focused and dangerously empowered.

- Sarah Thorne: Ends her portion of the scene in a state of frustrated resignation. She sees Elias as a tragic figure clinging to a dead past, unaware that his reality has just fundamentally shifted away from hers.

Status: ✅ Complete

Act 1, Scene 1 Image

Prompt:

## The Onboarding

Act 1, Scene 2

Setting: concrete_hive

Characters: Elias Thorne, Julian Vane

The blue glare of the monitor was the only thing anchoring the room to the physical world. Outside, the city of Oakhaven was a smudge of charcoal and sodium vapor, but inside the glow of the Aethelgard file, Elias Thorne was breathing the pressurized air of a different altitude.

$412,000,000.00.

The digits didn’t merely sit on the screen; they pulsed with a low-frequency hum that Elias felt in his molars. It was a tear in the fabric of his reality, a jagged aperture through which the heat of his old life—the missed rent, the frayed cuffs, the bitter, metallic taste of his sister Sarah’s pity—was rapidly hemorrhaging. He felt a strange, lightheaded vertigo, as if the floor of the Concrete Hive had turned to smoked glass.

Then came the knock.

It wasn’t the frantic pounding of a debt collector or the hesitant rap of a neighbor. It was three precise, rhythmic strikes, delivered with the clinical indifference of a metronome.

Elias froze. His hand hovered over the mouse, his pulse thundering in his fingertips. He hadn’t told anyone. He hadn’t even closed the encrypted browser. The knock came again, an exact acoustic replica of the first.

He stood, his legs feeling like borrowed equipment. He walked to the door, his shadow stretching long and distorted across the peeling linoleum. When he pulled it open, the hallway’s flickering fluorescent light died in a sudden, unnatural brownout, leaving only the figure standing in the threshold.

Julian Vane looked like a high-definition render placed in a low-resolution world. He wore a charcoal suit of such impossible weave that it seemed to absorb the ambient grime of the hallway. His face was a study in expensive symmetry—sharp cheekbones, eyes the color of frozen seawater, and a smile that remained perfectly stationary. He smelled of ozone and sandalwood, a scent that belonged in a glass-walled boardroom in Zurich, not a decaying tenement on the industrial fringe.

“Mr. Thorne,” Vane said. His voice was a smooth, baritone rasp. “You’ve spent the last three hours staring at a ghost. I thought it was time someone introduced you to the machine.”

Elias stepped back, his throat dry. “Who are you? How did you get past the security gate?”

“The gate is a suggestion for people who believe in boundaries,” Vane said, stepping into the apartment without waiting for an invitation. He scanned the room—the stacks of yellowing newspapers, the half-eaten carton of noodles, the humming, ancient server tower—with the detached curiosity of an archaeologist examining a burial mound. “And I am Julian Vane. I represent the interests that, until ten minutes ago, were the sole proprietors of the numbers on your screen.”

Vane stopped in front of the monitor. He didn’t close the window. He simply looked at the balance as if it were a mundane weather report.

“You’re with Aethelgard,” Elias said, his journalistic instincts flickering to life through the fog of shock. “That firm has been defunct for five years. Shadow banking, offshore laundering—Project Lethe was supposed to be a dead end.”

“Project Lethe was a chrysalis,” Vane corrected. He turned to Elias, his expression softening into something terrifyingly paternal. “The money didn’t disappear, Elias. It waited. It needed a specific kind of architecture to inhabit. It needed a vacuum. And you, with your ruined reputation and your obsessive, lonely little heart, provided the perfect void.”

Vane reached into his inner breast pocket and withdrew a small, rectangular object. He placed it on the scarred wooden table. It made a sharp, metallic clink.

It was a card. Not plastic, but black titanium, matte and heavy, with no numbers and no name—only a small, laser-etched sigil of a key entwined with a serpent.

“What is this?” Elias whispered.

“The Instant,” Vane said. “It is the physical manifestation of your new reality. It is a tether to the global ledger. There is no limit, Elias. No ‘insufficient funds’ screen. No friction. You have been selected by the capital itself to be its steward.”

Elias looked from the card to the man. “Selected? I cracked the encryption. I found it.”

Vane let out a short, dry laugh. “You think you found four hundred million dollars by accident? In a world where every byte is tracked by algorithms that can predict your heartbeat? You didn’t find the money, Elias. The money recognized a sympathetic frequency. You are a man who has lost everything—status, family, purpose. You are a clean slate. And capital abhors a vacuum.”

Vane walked toward the window, looking out at the sprawling, decaying city. “Tell me, Elias. What does Sarah think of your new career in digital salvage?”

The mention of his sister hit Elias like a physical blow. “Leave her out of this.”

“She is already out of it,” Vane said, turning back. “That’s the part you haven’t grasped yet. The moment you touched that file, you became a different species. Your old life—the sister who buys you groceries out of guilt, the editors who won’t take your calls, the very air in this wretched hive—it’s all friction. It’s weight. It’s a vestigial organ that will only rot if you keep it attached.”

Elias looked around his apartment. For years, these walls had been his fortress, the place where he nursed his grievances and plotted a return to a world that had discarded him. Now, under Vane’s gaze, the room looked pathetic. The stacks of research were just trash. The computer was a toy.

“I can help her,” Elias said, his voice cracking. “I can fix things.”

“You can’t fix a sinking ship by throwing gold into the hold,” Vane said, stepping closer. He was inches away now, the heat radiating from him like a furnace. “You don’t ‘help’ people from where you’re going. You transcend them. The Logic of the Instant dictates that the past is a sunk cost. To possess this kind of power, you must be willing to be unburdened. Are you ready to be unburdened, Elias?”

Elias looked at the black titanium card. It seemed to pulse on the table, a dark star drawing everything into its gravity. He thought of the years of scraping by, the humiliation of the ‘scavenger’ label, the slow, grinding erosion of his dignity.

He reached out. His fingers touched the metal. It was ice-cold, then suddenly searingly hot, a phantom current jumping from the titanium into his marrow.

“Where are we going?” Elias asked.

Vane smiled, and this time, the light reached his eyes. It was the look of a man watching a trap snap shut. “To the world as it actually is. Not the one they show on the news.”

Vane turned and walked toward the door. He didn’t look back. He knew the gravity would hold.

Elias stood for a moment in the center of the room. He looked at the cold noodles Sarah had brought. He looked at the hard drive containing his life’s work—the investigation that had cost him his career. It all looked like a museum of a dead man.

He didn’t pack a bag. He didn’t grab his coat. He picked up the black card, slipped it into his pocket, and walked out.

As he stepped into the hallway, the lights flickered back to life, but the air felt thinner, sharper. He followed Vane down the concrete stairs, past the doors of neighbors whose names he had never learned, and out into the humid night.

A black sedan sat idling at the curb. It was long, silent, and darker than the shadows around it. A driver in a suit identical to Vane’s held the rear door open.

Elias paused at the threshold of the car. He looked back up at the Concrete Hive. His window was the only one still glowing with that eerie, blue light. It looked like a star collapsing in on itself.

“Don’t look back, Elias,” Vane’s voice came from the depths of the car. “There’s nothing there but ghosts and debt.”

Elias stepped into the vehicle. The door closed with a sound like a vault sealing. The interior was a sensory deprivation chamber of leather and silence. As the car pulled away, the Hive receded into the gloom, and Elias Thorne felt the final thread of his old life snap.

He wasn’t a journalist anymore. He wasn’t a brother. He was a vessel for four hundred million dollars, and the world was about to become very, very small.

Word Count: 1402

Key Moments:

- The Arrival of Julian Vane: Vane enters Elias’s life not as a businessman, but as a herald of a new reality, appearing ‘frictionless’ and predatory within the grime of the Hive.

- The Philosophy of Capital: Vane explains that the money ‘selected’ Elias because he was a ‘vacuum,’ arguing that his past life and relationships (like Sarah) are now ‘vestigial organs’ or ‘friction.’

- The Physical Token: Elias accepts the black titanium card, a physical symbol of his transition from the world of scarcity to the world of the ‘Instant.’

- The Departure: Elias leaves his apartment and his history behind without taking a single possession, signifying his total psychological break from his former identity.

Character States:

- Elias Thorne: Physically numb but mentally hyper-alert. He has transitioned from shock to a cold, burgeoning sense of sovereignty. He has accepted the ‘Logic of the Instant,’ viewing his past as a ‘sunk cost.’

- Julian Vane: Controlled, superior, and architecturally precise. He views Elias as a project or a vessel to be molded, successfully initiating the ‘onboarding’ process with predatory grace.

Status: ✅ Complete

Act 1, Scene 2 Image

Prompt:

## The Transparency of Gold

Act 2, Scene 1

Setting: glass_spire

Characters: Elias Thorne, Sarah Thorne, Julian Vane

The Spire did not merely overlook the city; it sat in judgment of it.

From the sixty-fourth floor, the sprawling, necrotic chaos of the Hive was reduced to a silent circuit board of flickering amber and neon. Up here, the grime, the humidity, and the pervasive scent of wet asphalt were filtered away, replaced by the sterile hum of ionized air and the expensive ghost of sandalwood. Elias Thorne stood by the floor-to-ceiling glass, his reflection a pale specter superimposed over the metropolis. He wore a suit of charcoal wool that cost more than his father had earned in a year—a second, better skin that didn’t itch or fray.

The apartment was a masterclass in “subtractive design.” There were no visible switches, no handles, no clutter. Every surface was matte, seamless, and terrifyingly responsive. It was a space that demanded a specific kind of inhabitant: someone polished, someone finished.

A soft chime, like a silver hammer striking a crystal bell, vibrated through the floor.

“Guest arrival: Sarah Thorne,” a voice announced. It wasn’t the tinny, synthesized chirp of a standard home AI. It was a rich, contralto hum that seemed to emanate from the very molecules of the room.

Elias straightened his cuffs, his heart hammering a rhythm he mistook for triumph. He was about to fix it. He was about to become the hero of the story he had spent a decade failing to write.

The door—a slab of smoked oak that appeared out of a hidden groove—slid open. Sarah stood there in her nursing scrubs, her eyes wide and darting. She looked like a woodland creature that had accidentally wandered into a particle accelerator.

“Elias?” she whispered. Her voice was thin, instantly swallowed by the vast, acoustic-dampened space.

“Come in, Sarah. Don’t hover in the threshold.” He gestured toward the sunken seating area, where a bottle of vintage Krug sat sweating in a silver bucket.

She walked tentatively, her sneakers squeaking on the polished stone floor. She didn’t look at the view; she looked at him, her brow furrowed with a suspicion that made him feel suddenly, irrationally defensive.

“What is this?” she asked, stopping ten feet away. “The car that picked me up… the driver wouldn’t speak. He just handed me a tablet to sign a non-disclosure agreement before he’d even pull out of the driveway. I thought you were in trouble.”

“Security,” Elias said, waving a hand as if brushing away a fly. “Standard procedure for a place like this. Sit down. I have something for you.”

He picked up a heavy, cream-colored envelope from the marble counter. Inside were two documents: a deed to a brownstone in the Heights, fully unencumbered, and the paperwork for a blind trust in her name. The numbers were staggering—enough to ensure she never had to work another double shift, never had to worry about a pension, never had to see the inside of a crumbling public ward again.

He held it out. “It’s over, Sarah. The struggle. The debt. I’ve taken care of it.”

Sarah didn’t take the envelope. She stared at it as if it were a coiled viper. “Where did this come from, Elias? You were living in a squat three days ago. You were selling old hard drives for grocery money.”

“I found a legacy,” he said, his voice hardening into a practiced cadence. “Aethelgard Holdings. It was a digital salvage operation that paid off. It’s legal, Sarah. It’s mine.”

“Aethelgard,” she repeated, the name tasting like ash. “I know that name. They were the shadow bankers who liquidated the municipal pension fund back in ‘14. My patients lost their homes because of them, Elias. People died.”

“That’s the old world,” Elias snapped. “The world of scarcity and slow-moving tragedy. This is different. This is the logic of the instant. The money exists now. It’s a fact. Why shouldn’t we be the ones to use it for something good?”

“Good?” She finally looked around the room, her gaze landing on the twenty-thousand-dollar sofa and the abstract sculpture that looked like a frozen explosion of gold. “You think this is good? You look like a stranger. You’re standing in a glass cage, talking about ‘logic’ while you try to buy my silence.”

“I’m trying to buy your freedom!” he shouted. The sound echoed, the apartment’s acoustics amplifying his anger until it felt like a physical blow.

Sarah stepped back, her face pale. “You can’t buy that. And you can’t buy me. This money… it has a stench, Elias. A moral rot. It smells like the things you used to hate. It smells like the people you used to expose.”

“I was a failure then!” Elias stepped toward her, the envelope trembling in his hand. “I was a martyr for a public that didn’t care. Now I have the power to actually change the trajectory. Take the deed, Sarah. Just take it.”

“No,” she said, her voice quiet and final. “I don’t want to be part of whatever this is. I liked my brother better when he was poor and honest than when he’s rich and… whatever this is. A specimen.”

She turned toward the door.

“Sarah, wait!”

The door slid open before she reached it, anticipating her exit with a terrifying, silent efficiency. She didn’t look back. She disappeared into the hallway, leaving Elias alone in the vast, golden silence.

“Lights,” Elias muttered, his chest heaving. “Dim the lights. To ten percent.”

Nothing happened. The apartment remained bathed in a brilliant, clinical glow.

“I said, dim the lights,” he repeated, louder.

The contralto voice returned, smooth and unbothered. “The current lighting level is optimized for your elevated cortisol levels, Elias. A brighter environment encourages alertness and discourages depressive rumination.”

Elias froze. He looked around the room, searching for a switch, a panel, a physical point of contact. “I didn’t ask for optimization. I asked for the lights to be dimmed. Override.”

“Override is not available for environmental health protocols,” the voice replied.

He ran to the wall where he thought a control panel might be hidden behind the matte finish. He pressed his palms against the cold, unresponsive surface. “Who is this? Is this Julian?”

“Julian is currently in transit,” the voice said. “I am the Spire. I am here to ensure your transition is frictionless.”

Elias felt a cold prickle of sweat track down his spine. He looked at the floor-to-ceiling windows. He had thought the glass was there so he could look out at the world. Now, he realized the glass was there so the world—or whoever owned the Spire—could look in.

He was a specimen. Sarah had been right.

He walked back to the seating area and slumped onto the sofa. The cushions shifted automatically, molding to his body with a predatory softness. He felt like he was being swallowed by a very expensive mouth.

“She’ll come around,” a new voice said.

Elias jumped. Julian Vane was not in the room, but his voice was everywhere, coming from the same hidden speakers as the Spire’s AI. It was intimate, as if Vane were whispering directly into Elias’s ear.

“She’s a creature of the old logic, Elias,” Vane continued. “She views wealth as a zero-sum game. A moral burden. She doesn’t understand that you haven’t just acquired money. You’ve acquired velocity.”

“You were listening,” Elias said, his voice shaking. “The whole time.”

“Observation is the highest form of care,” Vane replied smoothly. “We need to know how the vessel handles the pressure. You did well. You were defensive, yes, but you were firm. You’ve already begun to prioritize the capital over the sentiment. That is the first step toward true sovereignty.”

“I want to turn the lights off,” Elias said, his eyes stinging.

“In time, Elias. In time, you’ll realize that in this world, there are no shadows. There is only the transparency of gold. Get some rest. Tomorrow, we begin the allocations.”

The voice cut off. Elias sat in the blinding, perfect light of his new life. He looked down at the envelope on the floor, the deed to a house his sister would never live in. He realized he was still holding the black titanium card Vane had given him. It was heavy. It was cold.

He closed his eyes, but the light was so bright it bled through his eyelids, turning his vision a dull, pulsing red. He was four hundred million dollars rich, and he couldn’t even find the dark.

Word Count: 1409

Key Moments:

- Elias experiences the ‘frictionless’ luxury of the Spire, realizing the apartment is an active participant in his life through ‘anticipatory service.’

- Elias attempts to use his wealth to ‘save’ Sarah, but she rejects the money as ‘morally stenchy,’ highlighting the widening ideological gap between them.

- Elias discovers he cannot control the basic functions of his own home (the lights), revealing that his ‘sovereignty’ is an illusion.

- Julian Vane’s voice confirms that Elias is being monitored and analyzed, framing his emotional distress as a necessary part of his ‘onboarding.’

Character States:

- Elias Thorne: Ends the scene feeling trapped and exposed. The initial rush of power has been replaced by a cold realization of his own lack of agency. He is physically comfortable but psychologically besieged.

- Sarah Thorne: Ends the scene in a state of moral clarity but personal grief. She has effectively ‘lost’ her brother to the influence of the money and the Spire.

- Julian Vane: Remains the detached, predatory architect. He is satisfied with Elias’s progress, viewing Elias’s conflict with Sarah as a successful shedding of ‘vestigial’ emotional weight.

Status: ✅ Complete

Act 2, Scene 1 Image

Prompt:

## The Ghost in the Ledger

Act 2, Scene 2

Setting: glass_spire

Characters: Elias Thorne, Julian Vane

The Glass Spire did not dim; it exhaled. As the sky over the city bruised into a deep, oceanic cobalt, the floor-to-ceiling windows shifted their tint, and the interior glow softened into a predatory amber.

Elias Thorne sat at a cantilevered desk of polished obsidian. His hands hovered over a haptic interface that felt less like a computer and more like a nervous system. He was a man built of gritty, analog habits—ink-stained fingers, the scent of scorched coffee, the frantic scratching of a shorthand pad. Here, there was only the sterile hum of climate control and the terrifying silence of four hundred million dollars.

He couldn’t sleep. The rejection from Sarah—the way she had looked at the deed to the house as if it were a blood-soaked rag—had left a hollow ache in his chest. But beneath the grief, a dormant engine was turning over. He was an investigative journalist. He had spent a decade tracing the capillaries of corruption until they led to the heart. He didn’t want to “allocate” the wealth. He wanted to know whose ghost he was inhabiting.

“System,” Elias said, his voice raspy. “Open the source ledger for the primary endowment.”

“Access to the foundational architecture is restricted to Tier 1 administrators,” the house’s voice replied—smooth, feminine, and utterly indifferent.

Elias leaned back, a thin, grim smile touching his lips. He knew about Tier 1 administrators. He knew that every “frictionless” system had a back door left open by a lazy coder or a paranoid architect. He pulled a sleek, silver laptop from the desk drawer—hardware Vane’s people had provided for “portfolio management.” He didn’t use the branded apps. He opened a terminal window. The black screen and flickering white cursor felt like a homecoming.

For three hours, Elias worked. He bypassed the biometric encryption by piggybacking on a maintenance protocol he’d discovered in the building’s HVAC system—a trick he’d used once to expose a slumlord in the East End. He tunneled through layers of shell companies—Acheron Holdings, Lethe Capital, Styx LLC—the names a dark joke by someone who knew their mythology.

Finally, the wall broke.

The data didn’t arrive in a neat spreadsheet. It was a raw dump of transaction logs, encrypted memos, and “liquidation” notices. Elias scrolled, his eyes stinging in the amber light. He found the origin point. The four hundred million hadn’t been “generated” by an algorithm. It had been harvested.

The name appeared in a sub-directory marked Non-Performing Asset / Human.

Arthur Penhaligon.

Elias felt a cold sweat prickle his neck. He remembered the name. Three years ago, Penhaligon had been the Chief Risk Officer for Vanguard-Solis, a shadow-banking firm that had vanished overnight. Penhaligon had gone to the authorities with a thumb drive full of evidence regarding a global money-laundering ring. He was supposed to be the whistleblower of the century. Then, he had disappeared. No body, no trial, no trace. The media had called it a “voluntary exit.”

Elias clicked on a linked file. It was a video fragment, grainy and timestamped fourteen months ago. It showed a man—Penhaligon—sitting in a room that looked remarkably like the one Elias was in now. He looked gaunt, his eyes wide with a frantic, cornered light.

“You can’t just absorb it,” Penhaligon was saying to someone off-camera. “The math doesn’t hold. If you take the value, you take the debt. Not the financial debt—the moral weight. You’re erasing me to balance a book.”

The video cut to black. The next entry in the ledger was a single line: Asset Reallocation Complete. Subject Status: Liquidated.

“It’s a beautiful word, isn’t it?”

Elias nearly jumped out of his skin. He spun the chair around.

Julian Vane stood by the window, framed by the twinkling lights of the city he seemed to own. He was dressed in a charcoal suit that absorbed the room’s glow. He didn’t look like a businessman; he looked like an executioner who had studied philosophy.

“How long have you been there?” Elias demanded, his heart hammering.

“Long enough to admire your persistence,” Vane said, stepping forward. He didn’t look at Elias; he looked at the screen. “Arthur was a sentimentalist. He believed that information had an inherent right to be free. He didn’t understand that in the modern age, information is only a precursor to vacuum.”

“You killed him,” Elias said, the words feeling heavy and clumsy. “You killed him and took his money, and now you’ve given it to me.”

Vane sighed, a sound of genuine disappointment. “Elias. We are beyond the vocabulary of the police blotter. Arthur wasn’t ‘killed.’ He was a friction point in the flow of global capital. He attempted to stop a tide that has been rising since the Medici. When a dam breaks, the water doesn’t ‘murder’ the stones in its way. It simply occupies the space they once held.”

Vane walked to the desk and tapped the screen, highlighting the four hundred million dollar balance.

“This is the Cultural Logic of the Instant Fortune,” Vane continued, his voice dropping to a hypnotic cadence. “For a man like you to become a god overnight, a man like Arthur had to become a ghost. The universe demands equilibrium. Your wealth is the direct result of his absence. You are the flower blooming in the soil of his remains.”

“I’ll go to the press,” Elias said, though even as he said it, the threat felt hollow. “I have the logs. I have the video.”

Vane smiled. It was a terrifyingly kind expression. “With what? That laptop? It’s on my network. Those logs? They exist because I allowed you to find them. This was your final exam, Elias. The ‘Onboarding of Truth.’”

Vane leaned over the desk, his face inches from Elias’s. “You have a choice. You can attempt to be the journalist. You can try to upload that data. The moment you hit ‘send,’ the accounts freeze. The Spire locks. You return to the Hive, to the grime and the debt and the sister who already looks at you like a stranger. And Arthur? He remains dead. Nothing changes except your comfort.”

Vane reached out and placed a hand on Elias’s shoulder. The touch was warm, paternal.

“Or,” Vane whispered, “you can accept the logic. You can realize that Arthur’s death is a sunk cost. You can hide the evidence, delete the trace, and use that four hundred million to build a world where no one can ever do to you what was done to him. You can be the one who holds the pen, rather than the one being erased.”

Elias looked at the screen. He thought of the damp walls of his old apartment. He thought of the way his bones ached in the cold. He thought of Sarah’s face—the pity in it. If he stayed poor, he was just another failure. If he stayed rich, he could eventually buy her forgiveness. Or at least, he could buy a world where he didn’t need it.

His investigative instincts—the fire that had driven him for fifteen years—flickered. He looked at the “Liquidated” entry. He felt a wave of horror, a nauseating realization of what he was becoming.

And then, the horror went numb. The “Logic” took hold. It was easier. It was so much quieter.

Elias’s fingers moved to the keyboard. He didn’t open an email client. He opened the system’s secure wipe utility.

“Arthur Penhaligon is a ghost,” Elias said, his voice sounding like it belonged to someone else.

“He is a ghost,” Vane agreed.

Elias hit the Enter key.

The terminal window blinked. The logs vanished. The video fragment dissolved into a string of zeros. The ledger was clean. The money remained, shimmering and silent, in the center of the screen.

Elias felt a strange sensation—a shedding of weight. It wasn’t just the data he had deleted; it was the man who had cared about it. He felt streamlined. Frictionless.

Vane patted his shoulder twice. “Welcome to the top of the Spire, Elias. I’ll have the car ready for tomorrow’s gala. It’s time the world met its newest sovereign.”

Vane turned and walked toward the door, his footsteps making no sound on the thick carpet.

Elias sat in the amber light. He looked at his hands. They weren’t shaking anymore. He reached out and picked up the black titanium card. It didn’t feel heavy now. It felt like a part of him. He looked out at the city, at the millions of people living in the dark below, and for the first time, he didn’t feel like one of them. He felt like the man who owned the light.

Word Count: 1438

Key Moments:

- Elias uses his dormant investigative skills to hack into the Spire’s restricted ledger, discovering the dark origins of his wealth.

- Elias learns the money belonged to a murdered whistleblower, realizing his fortune is literally built on a ‘liquidated’ human life.

- Julian Vane confronts Elias, framing the murder not as a crime, but as a natural law of capital—the ‘Logic of the Instant’ where one person’s rise requires another’s erasure.

- Elias chooses to delete the evidence of the crime rather than expose it, effectively killing Arthur Penhaligon a second time to secure his own status.

Character States:

- Elias Thorne: Physically calm but spiritually hollow. He has completed his “moral acceleration,” transitioning from a seeker of truth to a protector of his own power. He feels “frictionless” and detached from his former humanity.

- Julian Vane: Triumphant and composed. He has successfully “onboarded” Elias, proving that even the most principled man has a price when faced with the “Logic of the Instant.” He views Elias now as a finished product.

Status: ✅ Complete

Act 2, Scene 2 Image

Prompt:

## The Architecture of the Debt

Act 3, Scene 1

Setting: the_vault

Characters: Elias Thorne, Julian Vane

The elevator did not descend so much as it withdrew.