The Capsaicin Paradox: Biological Honesty and the Social Poison of the Spicy Food Semiotic Field

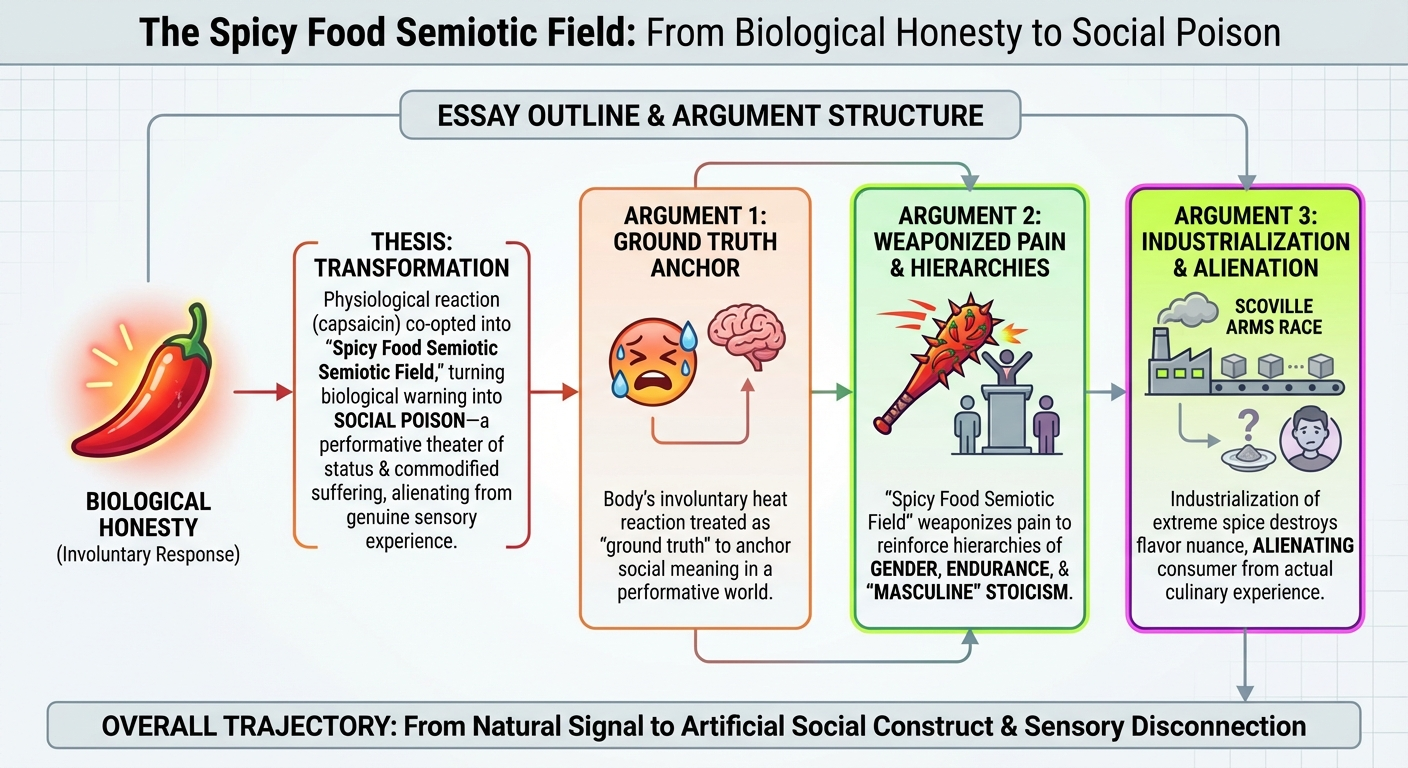

The biological honesty of the capsaicin response—the involuntary flush, the beads of sweat, the dilated pupils—is precisely what makes it such fertile ground for social semiotics. Because these reactions are difficult to fake, they are treated as “honest signals” of an internal state. Yet this very treatment reveals a deeper philosophical move: what we call “biological honesty” is itself a form of strategic essentialism—a collective decision to treat the body’s signals as ground truth so that we have a fixed reference point in an otherwise endlessly performative social world. The body’s reactions are not inherently more truthful than any other sign; we designate them as such because a semiotic system requires an anchor, a place where interpretation agrees to stop. This anchoring is not a discovery about nature but a cultural commitment—one that quietly underwrites every social meaning we subsequently extract from the burn.

However, the moment these signals are observed by another, they are pulled into the Semiotic Field, where they are no longer just physiological events but symbols to be interpreted.

The sensation of heat from a chili pepper is a biological absolute—a chemical interaction between capsaicin and the TRPV1 receptors that signals a warning of thermal pain. This is what we might call “biological honesty”: the body reacting to a perceived threat with a predictable, physiological response. However, once this sensation enters the human social sphere, it is immediately transmuted into something far more complex. It becomes a “social poison,” where the raw experience of pain is filtered through layers of cultural meaning, gendered performance, and status signaling. To understand this transformation, we must map the Spicy Food Semiotic Field—a conceptual space where the physiological reality of the burn collides with the symbolic weight of its consumption.

The Biological Honesty of Heat

At its core, the capsaicinoid response is an evolutionary defense mechanism—and a remarkably precise one. Plants of the genus Capsicum developed capsaicin not as a broad-spectrum toxin but as a strategy of Directed Deterrence: a molecular key shaped to fit one specific lock. Capsaicin binds to the TRPV1 vanilloid receptor—a thermosensor calibrated to fire at temperatures above 43°C—and activates it at room temperature. In effect, the molecule lies to the mammalian nervous system, convincing it that the mouth is being scalded when no thermal event is occurring. Birds, lacking the specific TRPV1 configuration sensitive to capsaicin, consume the fruit and disperse the seeds intact through their digestive tracts. The evolutionary elegance is striking: the plant does not poison indiscriminately but engineers a targeted sensory hallucination, exploiting the mammalian pain architecture to redirect its reproductive future through avian vectors. This is the first layer of biological honesty—though, as we shall see, even calling it “honesty” requires qualification, since the signal is, at the molecular level, a sophisticated deception.

When a human bypasses this warning, the resulting sensation acts as a profound embodiment anchor. Unlike the subtle nuances of flavor, the heat of a habanero or a ghost pepper demands immediate, total interoceptive awareness. It forces the consciousness back into the physical frame, demanding attention to the mouth, the throat, and the rising internal temperature. In an era of digital abstraction, this “honest” pain provides a grounding reality that cannot be ignored or intellectualized away. Yet even here, a crucial philosophical nuance intervenes—what we might call the nociceptive-interpretive gap. The TRPV1 receptor performs nociception: a straightforward chemical-to-electrical transduction, converting the presence of capsaicin into an ion channel event and a nerve impulse. But pain—the burning, the panic, the urge to reach for milk—is not the signal itself; it is the brain’s interpretation of that signal, constructed through layers of context, memory, and expectation. Even at the most “biological” level, the body is not simply reporting; it is already narrating. The supposedly raw datum of the burn is, from its very first synapse, an act of meaning-making. This gap between transduction and experience is what makes the entire semiotic apparatus possible: if the signal were truly unmediated, there would be nothing for culture to rewrite.

Physiologically, this heat serves several utilitarian functions. It acts as a built-in appetite throttle, increasing satiety and slowing the pace of consumption—a natural defense against overindulgence. Furthermore, its role as a vasodilator and irritant triggers a sinus-clearing mechanism, facilitating respiratory relief.

The transition from pain to pleasure—the “acquired taste”—is driven by the body’s own compensatory mechanisms. As the TRPV1 receptors signal intense heat, the brain responds by releasing a flood of endorphins and dopamine to mitigate the perceived trauma. This creates the “endorphin loop,” where the initial distress is followed by a mild euphoria. Over time, the brain learns to associate the burn not with damage, but with the subsequent neurochemical reward, transforming a biological warning into a sought-after culinary experience. But there is a deeper physiological process at work beyond mere associative learning: chili bleaching, the functional desensitization of TRPV1-expressing neurons through repeated capsaicin exposure. With chronic stimulation, these neurons undergo a depletion of neuropeptides such as Substance P and, in some cases, a reversible degeneration of their peripheral terminals. The receptor doesn’t “toughen up”; it is effectively silenced. What society reads as “toughness”—the stoic consumption of a Carolina Reaper without visible distress—may simply be the result of bleached receptors, a neurological quiet mistaken for a moral quality. And the body’s encounter with capsaicin does not end at the palate. TRPV1 receptors line the entire gastrointestinal tract, from esophagus to rectum, and capsaicin activates them at every station along the way. This “second burn”—the intestinal cramping, the unmistakable rectal sting hours later—is the plant’s evolutionary parting gift, a final reminder that the directed deterrence strategy extends well beyond the mouth. It is a sensation rarely discussed in polite company, yet it completes the biological circuit: the mammalian body is warned at entry and at exit, bookending the digestive journey with the same molecular lie.

Benign Masochism and the Psychology of the Acquired Taste

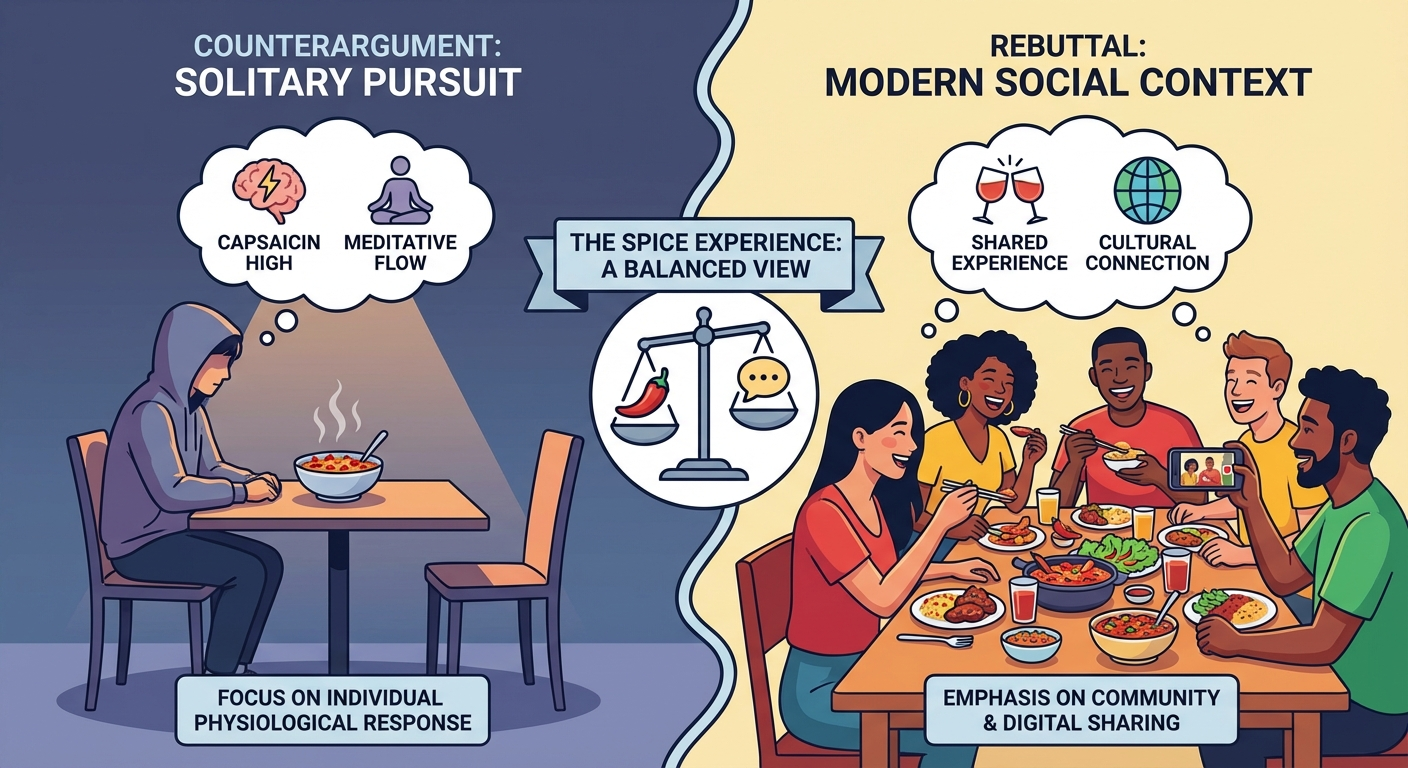

Yet the endorphin loop and receptor desensitization, powerful as they are, do not fully explain why humans seek out the burn in the first place. After all, the body produces compensatory endorphins in response to many forms of pain—stubbing a toe, touching a hot stove—without those experiences becoming objects of craving. The missing piece is not neurochemical but cognitive, and it was most precisely articulated by the psychologist Paul Rozin, who coined the term “benign masochism” to describe the peculiar human capacity to derive pleasure from sensations that the body’s alarm systems register as threats. Rozin’s insight is that the pleasure of capsaicin is not merely the endorphin afterglow that follows the pain; it is the simultaneous awareness that the pain is real and the danger is not. The higher-order cortex—the evaluative, contextualizing brain—monitors the TRPV1 alarm and performs a rapid override: the mouth is screaming “fire,” but there is no fire; the nociceptive system is reporting tissue damage, but no tissue is being damaged. It is this cognitive gap between the body’s conviction and the mind’s knowledge that generates the characteristic thrill. The pleasure derives, in significant part, from the psychological satisfaction of having tricked one’s own evolutionary hardware—a felt sense of mastery over the body’s most ancient and authoritative warning system. The eater is not merely enduring pain; they are staging a private rebellion against the tyranny of their own reflexes, and winning.

What Rozin identified, in effect, is the structure of a “safe threat”—an experience that provides all the physiological markers of a genuine biological crisis (the racing heart, the sweating, the flood of stress hormones) without any of the biological cost. This is the same architecture that underlies the appeal of roller coasters, horror films, and skydiving: the body is fully mobilized for an emergency that the mind knows will not arrive. But capsaicin occupies a unique position within this category, because the threat is not external and environmental but internal and somatic—the danger signal originates from inside the body itself, from the very tissue of the mouth, making the override feel more intimate, more like a genuine contest between self and self. This psychological dimension is the critical bridge between the biological story told above and the social story that follows. The endorphin loop explains how pain becomes tolerable; benign masochism explains how it becomes desirable. And it is precisely at the moment when the individual discovers this private pleasure—this quiet triumph of cognition over nociception, of the knowing mind over the screaming body—that the experience becomes available for social interpretation. The internal mastery must be performed to be witnessed, and once it is witnessed, it enters the semiotic field. The private rebellion becomes a public signal. The body’s honest alarm, already overridden by the individual’s own cognition, is now ready to be overwritten again—this time by the collective scripts of culture, status, and identity.

The Social Layer and the Semiotic Field

This is where the “Social Poison” of interpretive overfitting begins. In a social context, we rarely allow a physiological reaction to simply be; we over-interpret it, assigning intent and character to involuntary biological processes. The raw data of a sweating brow is overwritten by cultural scripts, leading to two primary, often conflicting, narratives.

The Performance Hypothesis

The first narrative is the Performance Hypothesis, which views the consumption of extreme heat as a calculated display of status or belonging. In this framework, the visible struggle with spice is seen as a performative act—a “masochistic” display designed to signal toughness, worldliness, or membership in a specific subculture (such as the “chili-head” community). Here, the “honesty” of the biological response is ironically subverted; the very fact that the reaction is involuntary makes it the perfect stage for a performance of endurance. The consumer isn’t just eating; they are demonstrating their ability to colonize their own biological pain for social capital.

What gives this performance its peculiar credibility is a dynamic that biologists call the Handicap Principle and game theorists call costly signaling: a signal is trustworthy precisely because it is expensive to produce. A peacock’s tail is convincing evidence of genetic fitness because growing and carrying it is a genuine metabolic burden; a bluff would collapse under the weight. The spicy-food performance operates on the same logic. The visible struggle—the flushed skin, the watering eyes, the involuntary gasp—is not a flaw in the display; it is the display. It works as a status signal precisely because it hurts. The pain is the price of admission, and only those who value the resulting social capital enough to pay it, or who possess a naturally high capsaicin tolerance that lowers the cost, will sit down at the table and order the Carolina Reaper. Someone who merely claims to love extreme heat but blanches at the first bite gains nothing; the body’s involuntary betrayal exposes the bluff instantly. This is the deep irony at the heart of the Performance Hypothesis: the biological honesty of the capsaicin response—the very thing that seems to undercut a polished social performance—is what makes the performance credible in the first place. Because the cost cannot be faked, the signal cannot be counterfeited. The sweating brow is not a failure of composure; it is the receipt that proves the toll was paid.

The Toughness Hypothesis

The second narrative is the Toughness Hypothesis, which interprets spice tolerance as a proxy for moral or physical character. In many cultures, the ability to “handle” heat is conflated with grit, resilience, and even masculinity. Under this lens, the person who does not sweat or flush is seen as possessing a superior constitution. The biological variation in TRPV1 receptor density—a matter of genetic luck—is transformed into a moral trait. To have a high tolerance is to be “strong”; to struggle is to be “weak.” This hypothesis ignores the biological reality of desensitization and genetics, replacing it with a semiotic system where the tongue becomes a site of character judgment.

From a psychological standpoint, this conflation of tolerance with character is a textbook instance of the Fundamental Attribution Error—the well-documented tendency to attribute others’ behavior to stable dispositional traits (courage, weakness, discipline) while underweighting the situational and biological variables that actually explain the behavior. When an observer watches someone eat a scorpion pepper without flinching and concludes that this person is tough, they are performing precisely the attribution error that Lee Ross identified in 1977: mistaking a situational outcome—one shaped by prior exposure history, cultural habituation, and, crucially, genetic endowment—for a window into the person’s character. The error is compounded by the fact that the biological substrate in question is not uniform across the population. The TRPV1 gene exhibits significant polymorphic variation: single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in and around the TRPV1 locus alter receptor expression levels, ion-channel sensitivity, and downstream signal amplification. Some individuals are born with a sparse distribution of functional TRPV1 receptors in their oral mucosa; others carry variants that produce receptors with a higher activation threshold, requiring more capsaicin to trigger the same nociceptive cascade. What society codes as “strength”—the calm, unflushed consumption of extreme heat—may therefore be, in the most literal sense, a partial absence of sensory hardware: not a triumph of will over pain, but a quieter peripheral signal that never reached the volume the observer imagines was heroically suppressed. Conversely, the person who gasps and reaches for milk may possess a denser receptor field or a more sensitive channel variant—a richer sensory apparatus, not a weaker constitution. The Toughness Hypothesis thus performs a double inversion: it reads a genetic variable as a moral constant, and it rewards sensory deficit as though it were psychological surplus. By mapping the Fundamental Attribution Error onto the biology of TRPV1 polymorphism, we can see that the entire edifice of spice-as-character-test rests on a failure to distinguish between what the body is and what the person chooses—between the hand one is dealt and the way one plays it.

The Sensory Semiotic Triad: Spicy, Sour, and Bitter

To fully appreciate the unique position of heat in the social hierarchy, we must compare it to other intense sensory experiences. We can conceptualize a Sensory Semiotic Triad consisting of the spicy, the sour, and the bitter. While all three involve a degree of “acquired” appreciation, they occupy vastly different roles in the theater of social interaction.

Spicy and sour sensations are inherently public dramas. Both trigger immediate, involuntary, and highly visible physiological responses—the “sour face” (puckering of the lips, squinting of the eyes) and the “spicy flush” (sweating, gasping, redness). These signals are ambiguous; they can represent either distress or intense pleasure, creating a semiotic gap that the observer must fill. Crucially, these signals are what semioticians in the Peircean tradition would call polysemic—they carry multiple, competing meanings simultaneously. A flushed face and watering eyes could signify genuine agony, masochistic pleasure, performative bravado, or the threshold moment between surrender and triumph. The observer cannot determine which meaning is “correct” from the signal alone, and it is precisely this semiotic ambiguity that serves as the engine of social co-optation. Because the sign underdetermines its meaning, it invites interpretation—and where interpretation is invited, social narratives rush in. The “sour challenge” or the “hot wing challenge” relies on this polysemic visibility to turn a private sensation into a shared spectacle, a text that the audience actively co-authors.

In contrast, bitterness remains largely a private signal. While a profound bitterness might cause a brief grimace, it lacks the sustained, escalating physical drama of heat or the sharp, contorting reflex of sourness—there is no progressive arc of visible suffering, no crescendo for an audience to track. More fundamentally, the bitter response is monosemic: it means one thing—rejection. The grimace at a bitter compound is read, almost universally, as aversion. There is no interpretive gap, no ambiguity about whether the person is suffering beautifully or performing resilience. The sign arrives pre-interpreted, and where there is no interpretive gap, there is no space for social narrative to colonize. A polysemic signal is an open text; a monosemic signal is a closed one. No one watches someone sip an intensely bitter espresso and wonders, “Is she in pain or ecstasy? Is this a feat of endurance?”—the grammar of the response simply does not pose the question.

Bitterness is therefore processed as a matter of internal preference—a “quiet” taste that one either enjoys or avoids, a private dialogue between the palate and the brain rather than a public broadcast of the body’s resilience. There is little social capital to be gained from “enduring” a bitter radicchio or a dark coffee in the same way one “conquers” a ghost pepper, because the bodily response to bitterness is neither legible enough to be read at a distance nor ambiguous enough to sustain competing interpretations. It is a preference, not a feat. The Triad thus reveals a principle: the social life of a sensation is proportional to the polysemy of its signal. Spicy and sour sensations become theaters of identity precisely because their signs are open to multiple readings; bitterness remains a private affair precisely because its sign is closed. The engine of social co-optation is not intensity alone—it is interpretive possibility.

Cultural Metastasis and Status Games

As the individual performance of spice consumption scales, it metastasizes into broader cultural tropes and identity politics. The semiotic field expands from the personal to the collective, where heat becomes a form of cultural capital. In this arena, the ability to navigate extreme spice is no longer just about personal toughness; it is a signal of worldliness and “authentic” engagement with the Other.

Spice as Cultural Capital and Authenticity Policing

In the globalized culinary market, spice levels are often used as a metric for authenticity. This leads to a form of authenticity policing, where the “true” version of a dish is defined by its proximity to a perceived threshold of pain. Diners may demand “Thai spicy” or “Indian spicy” as a way to distance themselves from the “diluted” or “Westernized” versions of a cuisine. Here, the heat is not just a flavor profile but a gatekeeping mechanism. To consume the heat is to prove one’s worthiness to participate in the culture, while the inability to do so is dismissed as a lack of culinary sophistication or a sheltered upbringing.

Yet this gatekeeping mechanism carries a deeper distortion that culinary scholars have identified as culinary orientalism: the reduction of an entire cuisine’s vast internal diversity to a single painful metric. To demand “Thai spicy” is to flatten a tradition in which many canonical dishes—the coconut-milk richness of tom kha gai, the delicate balance of pad see ew, the intentional mildness of a kanom jeen with mild fish curry—are designed to be gentle precisely because they provide contrast and balance within a meal structured around complementary sensations. Thai cuisine, like most complex culinary traditions, is an architecture of counterpoints: hot against cool, rich against sharp, intense against mild. To define its “authenticity” by its maximum capsaicin output is to mistake one voice in a choir for the entire performance—and, in doing so, to erase the compositional intelligence that makes the tradition worth celebrating in the first place. The semiotic field does not merely distort social dynamics; it flattens the very cuisines it claims to honor.

The narrowing runs deeper still. The semiotic field’s fixation on capsaicin-based heat as the metric of spice courage ignores the fact that pungency itself is a diverse sensory landscape. The numbing, electric mā (麻) of Sichuan peppercorns—produced by hydroxy-alpha-sanshool acting on mechanoreceptors rather than thermoreceptors—offers a form of intensity that is neurologically distinct from the capsaicin burn: it tingles, buzzes, and temporarily rewires the mouth’s sense of touch rather than its sense of temperature. The sharp nasal pungency of wasabi and horseradish, mediated by allyl isothiocyanate activating TRPA1 receptors in the sinuses, produces a fleeting, almost cerebral flash of pain that dissipates in seconds—a sensation with no sustained arc of visible suffering and therefore little utility for the endurance performances the semiotic field rewards. These alternative pungencies offer extraordinary complexity and cultural depth, yet they remain marginal to the dominant spice discourse precisely because they do not produce the prolonged, legible, polysemic spectacle that capsaicin does. The semiotic field, in other words, has not merely co-opted heat as a social signal; it has selected for a specific kind of heat—the kind that best serves performative endurance—and in doing so, has narrowed the sensory landscape even as it claims to celebrate adventurousness.

The Sophistication Paradox

This leads to the sophistication paradox: the claim that a high tolerance for heat signals a more refined and adventurous palate. Proponents of this view argue that spice enhances the complexity of a dish, yet at extreme levels, capsaicin objectively obliterates flavor nuance by overwhelming the taste buds and triggering a pain response that drowns out subtle aromatics. The paradox lies in the fact that the “refined” palate is often celebrating the very thing that prevents it from tasting the food’s finer details. The heat becomes a proxy for sophistication, even as it acts as a sensory blackout curtain—and the claim that extreme spice enhances one’s appreciation of a dish is, as a culinary analogy makes vivid, like saying you appreciate music more because you listen to it at 120 decibels. At that volume, the subtlety of the composition is not revealed but annihilated; what remains is not discernment but endurance. Game theory sharpens the absurdity further. Within the spicy food semiotic field, social capital is often valued more than the primary utility of the food itself, and the sophistication paradox is the point where this priority structure becomes fully visible. The consumer who orders the hottest item on the menu is executing a strategic trade-off: sacrificing the utility of flavor—the very thing that ostensibly defines culinary sophistication—in order to gain the utility of status. This is not a hidden cost; it is the entire mechanism. The diner pays in destroyed nuance and collects in social capital. Yet the sophistication claim requires that this trade-off remain unacknowledged, because the moment it is made explicit, the paradox collapses into plain contradiction: one cannot simultaneously claim to be maximizing gustatory appreciation while pursuing a strategy that systematically minimizes it. The “refined palate” is, in game-theoretic terms, a player who has optimized for a payoff (status) that is structurally incompatible with the payoff they advertise (taste)—and the sensory blackout curtain is not an unfortunate side effect of their strategy but its operative mechanism.

The Mayonnaise Proxy

Conversely, the absence of spice is weaponized through the “mayonnaise” stereotype. In contemporary social discourse, “mayonnaise” and “blandness” have become linguistic proxies for a specific type of identity—often associated with whiteness, lack of culture, or a fragile, unadventurous constitution. This stereotype functions as the inverse of the toughness hypothesis; if heat is grit, then mildness is weakness. By reducing complex cultural identities to their perceived tolerance for capsaicin, the semiotic field transforms a condiment into a tool for social categorization and identity-based derision. The “mayonnaise” label suggests a sensory sterility that is equated with a lack of historical or cultural depth, further entrenching the spicy food semiotic field as a primary site of modern social signaling.

The Industrialization of Suffering

The final stage in the evolution of the spicy food semiotic field is its commercialization and media-driven escalation—what might be termed the Hot-Wing Industrial Complex. In this phase, the private biological struggle is commodified and transformed into a public spectacle. Media platforms, most notably YouTube series like Hot Ones, have pioneered a new genre of interview where the physiological distress of the subject is the primary draw. The “biological honesty” of the capsaicin response is leveraged as a tool for “authentic” celebrity exposure; the theory being that a person cannot maintain a PR-managed facade while their TRPV1 receptors are screaming.

This industrialization relies heavily on Scoville-based marketing, where the heat level of a product is no longer a culinary choice but a competitive metric. Sauces are marketed with names that evoke violence, death, or insanity, turning the grocery aisle into a gauntlet of performative bravery. This turns the act of eating into a “challenge”—a discrete event designed for social media documentation. The biological struggle is no longer a byproduct of a meal; it is the product itself. Game theory reveals the structural logic driving this escalation. The Mayonnaise Proxy penalty described above—the social cost of being seen to prefer mild food—functions as a powerful negative payoff that reshapes the entire decision landscape. When the stigma attached to choosing mildness is sufficiently severe, the semiotic field collapses into what game theorists call a Pooling Equilibrium: a state in which all players, regardless of their private type (their actual capsaicin tolerance or preference), choose the same publicly visible action—extreme heat—because the cost of revealing oneself as mild-preferring exceeds the physical cost of enduring the burn. High-tolerance and low-tolerance individuals alike converge on the same fiery order, not because they share a preference but because the signaling environment has made the alternative socially untenable. The menu ceases to be a space of genuine choice and becomes a one-dimensional race to the top of the Scoville scale, where the only “safe” move is to match or exceed the group’s current threshold.

This pooling dynamic generates a Prisoner’s Dilemma at the heart of every shared meal. Consider two diners at a table: each might privately prefer a milder dish—one that would allow them to taste the food’s actual flavor profile and avoid the gastrointestinal aftermath. Yet each knows that choosing mildness while the other chooses heat will trigger the Mayonnaise Proxy penalty, coding them as the “weak” one in the pair. The dominant strategy for both players, therefore, is to choose spicy—not because it maximizes their individual gustatory utility, but because it minimizes their social risk. The result is a Pareto-inferior equilibrium: both diners end up suffering more than necessary, consuming food that overwhelms their palates and punishes their digestive tracts, when a world in which both chose mildly would have left each of them better off on every dimension except the one that matters in the semiotic field—status. The tragedy is structural, not personal. No single diner can unilaterally defect to mildness without bearing the full weight of the social penalty, and so the equilibrium holds, meal after meal, even though every participant in it would prefer a different world.

The commercial arm of the Hot-Wing Industrial Complex is locked into a parallel escalation that evolutionary biologists would recognize as a Red Queen race—the dynamic in which organisms must constantly evolve merely to maintain their current fitness relative to co-evolving competitors. As the pooling equilibrium drives consumers toward ever-higher Scoville counts, and as repeated exposure triggers the chili bleaching and TRPV1 desensitization described earlier, the spectacle’s impact erodes. A sauce that once produced dramatic, camera-ready suffering becomes, through habituation, merely uncomfortable—and a merely uncomfortable sauce generates no social media content, no viral moments, no signaling value. Brands must therefore innovate relentlessly toward more extreme formulations—higher capsaicinoid concentrations, novel cultivars like Pepper X and Apollo, synthetic capsaicin analogs—not to increase the level of social signaling their products provide, but simply to maintain it against the rising baseline of consumer tolerance. They are running to stand still. The result is an arms race between the human nervous system’s capacity for adaptation and the food industry’s capacity for chemical escalation, each driving the other forward in a feedback loop that has no natural resting point. The Scoville number on the label is not a measure of flavor; it is an index of how far the race has run.

Furthermore, this spectacle creates a new form of social cohesion: the ritual of suffering together. Whether in a viral “One Chip Challenge” or a group outing to a wing joint with a “wall of flame,” the shared experience of intense, non-lethal pain acts as a powerful bonding mechanism. This is a secular, sensory ritual where the participants prove their mettle and their shared identity through a collective descent into physiological chaos. The pooling equilibrium ensures that the ritual’s entry price keeps rising—what counted as a credible performance of toughness five years ago is now the table stakes, and the Prisoner’s Dilemma ensures that no individual participant can opt for a gentler experience without defecting from the group’s implicit social contract. By turning the burn into a stage for performing identity, and by locking both consumers and producers into interlocking escalation dynamics—the former trapped in a Pareto-inferior social equilibrium, the latter sprinting on the Red Queen’s treadmill—the Hot-Wing Industrial Complex ensures that the capsaicin paradox remains a central, if increasingly manufactured and increasingly painful, pillar of modern social interaction.

Conclusion: The Body as a Semiotic Surface

The journey from the TRPV1 receptor to the “Hot-Wing Industrial Complex” illustrates that the human body is never a closed biological system. It is a semiotic surface—a canvas upon which society projects its values of toughness, authenticity, and status. The “biological honesty” of a flush or a tear is immediately captured and recoded by the “social poison” of interpretation.

What this entire apparatus amounts to is a domestication of the absolute. The capsaicin response begins as a biological absolute—a raw, unmediated chemical scream from the TRPV1 receptor, a signal that evolved to mean one thing and one thing only: danger, stop, do not eat this. Yet we take this absolute and domesticate it, breaking it like a wild animal to the harness of social utility. We train it to mean toughness, authenticity, worldliness, belonging. We build elaborate semiotic architectures—the Performance Hypothesis, the Toughness Hypothesis, the Sophistication Paradox, the Hot-Wing Industrial Complex—all of which are, at bottom, cultural infrastructure for converting a biological emergency signal into a legible social currency. The “honesty” we attribute to the body’s involuntary response is not a property we discover in nature; it is a cultural layer we apply, a domesticating frame that makes sense of our peculiar desire to suffer for pleasure, for status, for the feeling of being fully alive in a body we can narrate to others. We do not honor the biological signal by reading it as honest; we tame it by doing so, rendering it safe enough to circulate in the economy of social meaning.

But domestication has a boundary, and that boundary reveals something essential about the entire enterprise. There exists a threshold—what we might call the point of semiotic collapse—where pain becomes so overwhelming that the social field dissolves entirely. Elaine Scarry, in The Body in Pain (1985), argued that intense physical pain is fundamentally world-destroying: it annihilates language, unmakes the sufferer’s capacity for symbolic thought, and reduces the human subject to pre-linguistic cries that carry no social meaning whatsoever. At the extreme end of the capsaicin spectrum—the point where a Carolina Reaper or a concentrated extract overwhelms not just the palate but the entire nervous system—we approach this threshold. The sufferer no longer performs toughness or signals authenticity; they simply hurt, in a way that is illegible to any semiotic framework. The flush is no longer a polysemic sign open to competing interpretations; it is the body in revolt, beyond narrative, beyond performance, beyond meaning. Language fails. The groan that escapes is not a social signal but a biological reversion—the organism stripped of its cultural clothing, returned to the pre-symbolic animal cry that no audience can decode as anything other than what it is.

The entire spicy food semiotic field, then, operates in the narrow space between two poles: the embodiment anchor—the point where capsaicin forces consciousness back into the body and makes the flesh available for social narration—and the threshold of semiotic collapse—the point where pain overwhelms all narration and the body ceases to be a legible text. Every hot wing challenge, every “Thai spicy” request, every Scoville-escalation arms race is a controlled flirtation with the biological real: an approach toward the abyss of unsymbolizable pain that never quite tips over the edge. The social utility of the burn depends entirely on maintaining this balance—enough pain to produce the honest, costly signal that the semiotic field requires, but not so much that the signal dissolves into the formless scream that no culture can metabolize. The domestication of the absolute is, in this light, an act of extraordinary precision: we must bring the wild animal close enough to feel its heat, but not so close that it devours us.

This machinery is not unique to capsaicin. We see identical patterns in the rise of extreme wellness rituals, such as the “cold plunge” or high-intensity interval training. In these contexts, the physiological shock—the “cold shock response”—is marketed and performed as a sign of superior discipline and mental fortitude. The shivering body, much like the sweating tongue, becomes a site of moral signaling. The raw data of the nervous system is consistently overwritten by the software of social expectation. And in each case, the same two boundaries apply: the experience must be intense enough to anchor the body as a legible semiotic surface, but not so intense that it crosses into the territory Scarry mapped—the zone where pain unmakes the world and the social field goes dark.

Ultimately, the capsaicin paradox reveals a fundamental human drive: the need to metabolize raw, chaotic sensation into structured, social meaning. We do not merely inhabit our bodies; we narrate them. But the narration is always precarious, always conducted at the edge of a silence that would swallow it whole. By transforming a plant’s defense mechanism into a cultural metric, we demonstrate that even our most visceral pains are never truly our own—they are always already part of the stories we tell about who we are and what we value. Yet the stories hold only so long as the pain remains domesticated. Beyond the last Scoville unit that language can metabolize lies the biological real—mute, absolute, and indifferent to every meaning we have tried to make it carry.

Comic Book Generation Task

Generated Script

Full Script

The Capsaicin Paradox

A philosophical and physiological descent into the “Spicy Food Semiotic Field,” exploring how a plant’s defense mechanism became a tool for human status, performance, and the eventual annihilation of language itself.

Characters

- Dr. Aris Thorne: Cynical, intellectual, detached observer of human folly. Narrator/Philosopher. The guide for the reader through the ‘Semiotic Field’. (A sharp-featured academic in a dark turtleneck and a lab coat that looks like a trench coat. Often seen in silhouette or half-shadow, holding a single chili pepper like a skull in a Hamlet soliloquy.)

- The Subject (Alex): Initially seeking social capital and ‘authenticity’, eventually reduced to primal biological reaction. Protagonist/Victim. The test subject for Dr. Thorne’s theories. (An average person whose appearance shifts from composed and trendy to a distorted, sweating, red-faced mess as the comic progresses. Wears a ‘Spice Seeker’ t-shirt.)

Script

Page 1

Row 1

- Panel 1: Close up on Dr. Thorne’s face, half-hidden in shadow. He holds a bright red Habanero between his thumb and forefinger.

- Dr. Thorne: “Meet the Capsicum. It doesn’t want to be eaten by you.”

- Caption: It begins with a lie. A molecular deception.

- Panel 2: A technical overlay of the Capsaicin molecule glowing in neon orange.

- Caption: It engineered a key. A molecular shape designed to fit a very specific lock. Row 2

- Panel 1: A surreal diagram of a human mouth. The TRPV1 receptors are depicted as glowing “fire alarms” on the tongue.

- Dr. Thorne: “The TRPV1 receptor. A thermosensor calibrated for 43°C. It’s there to tell you your mouth is on fire.”

- Panel 2: The Capsaicin molecule “plugging into” the receptor. Sparks of neon red fly off.

- Dr. Thorne: “The molecule lies. It tells the brain you are burning, even when the temperature hasn’t moved a degree.”

- Caption: DIRECTED DETERRENCE. Row 3

- Panel 1: A monochrome bird eating a chili pepper, looking completely unbothered.

- Dr. Thorne: “Birds lack the lock. They eat, they fly, they disperse the seeds. The plant’s reproductive future is secure.”

- Panel 2: Dr. Thorne looks directly at the reader, the chili pepper now closer to his own mouth.

- Dr. Thorne: “But humans? We heard the alarm… and we decided we liked the sound.”

Page 2

Row 1

- Dr. Thorne: “But humans? We heard the alarm… and we decided we liked the sound.”

- Panel 1: Alex (The Subject) sits at a lab table. He takes a bite of a pepper. He looks confident.

- Alex: “I can handle it. I’m a “Spice Seeker.””

- Panel 2: Close up on Alex’s eye. The pupil dilates. A single bead of sweat forms.

- Caption: BIOLOGICAL HONESTY. Row 2

- Panel 1: A split-screen. On one side, Alex’s brain is a chaotic mess of “FIRE!” warnings. On the other, a calm Dr. Thorne stands in a library.

- Dr. Thorne: “This is Benign Masochism. The body screams “Crisis,” but the mind knows it’s a ghost.”

- Panel 2: Alex’s nervous system is lit up like a neon circuit board. Endorphins are depicted as glowing blue droplets falling into a sea of red fire.

- Dr. Thorne: “The brain rewards the survival of a threat that never existed.”

- Caption: THE ENDORPHIN LOOP. Row 3

- Panel 1: Alex is now smiling through the pain, though his face is turning a light neon pink.

- Alex: “(Thinking) This… this feels amazing.”

- Panel 2: Dr. Thorne leans over Alex, looking like a shadow.

- Dr. Thorne: “You aren’t just eating, Alex. You’re staging a rebellion against your own evolutionary hardware. And you think you’re winning.”

Page 3

Row 1

- Dr. Thorne: “You aren’t just eating, Alex. You’re staging a rebellion against your own evolutionary hardware. And you think you’re winning.”

- Panel 1: Alex is at a table with friends. He’s eating a “Nuclear Wing.” He is visibly struggling—sweating, red-faced—but he’s holding a thumb up.

- Caption: THE PERFORMANCE HYPOTHESIS.

- Panel 2: Dr. Thorne stands in the background, leaning against a pillar, watching.

- Dr. Thorne: “The pain is the price of admission. If it didn’t hurt, it wouldn’t be a signal.” Row 2

- Panel 1: A diagram of a peacock’s tail overlays the restaurant scene.

- Dr. Thorne: “Biologists call it the Handicap Principle. A signal is only honest if it’s expensive.”

- Panel 2: Close up on Alex’s sweating brow. The sweat drops are labeled “THE RECEIPT.”

- Dr. Thorne: “You can’t fake the flush, Alex. That’s why they believe you’re “tough.”” Row 3

- Panel 1: Alex’s friends are cheering, but their faces are slightly distorted, like masks.

- Friend: “Man, you’re a beast! I could never do that.”

- Panel 2: Dr. Thorne holds a magnifying glass up to the scene.

- Dr. Thorne: “The biological event is over. Now, it’s just Social Poison. Interpretation has begun.”

Page 4

Row 1

- Dr. Thorne: “The biological event is over. Now, it’s just Social Poison. Interpretation has begun.”

- Panel 1: A comparison of two tongues. One has many glowing TRPV1 receptors (labeled “SENSITIVE”), the other has very few (labeled “BLEACHED”).

- Dr. Thorne: “Some are born with a sparse field. Others have burned their receptors into silence.”

- Panel 2: Alex is looking at a “Mayonnaise” jar with a look of disgust.

- Caption: THE MAYONNAISE PROXY. Row 2

- Panel 1: Alex is looking down at a person eating a mild korma. Alex looks “superior.”

- Alex: “Some people just don’t have the grit for real food.”

- Panel 2: Dr. Thorne points to a DNA helix.

- Dr. Thorne: “You’re mistaking a sensory deficit for a moral surplus, Alex. It’s not character; it’s polymorphism.” Row 3

- Panel 1: Alex is eating something so hot it’s literally glowing. He can’t see the food anymore; it’s just a white light.

- Caption: THE SENSORY BLACKOUT CURTAIN.

- Panel 2: Dr. Thorne sips a glass of water, looking bored.

- Dr. Thorne: “You claim it “enhances” the flavor. But you’re listening to Mozart at 120 decibels. You aren’t hearing the music; you’re just enduring the noise.”

Page 5

Row 1

- Dr. Thorne: “You claim it “enhances” the flavor. But you’re listening to Mozart at 120 decibels. You aren’t hearing the music; you’re just enduring the noise.”

- Panel 1: Alex is now a guest on a YouTube show. Cameras are everywhere. The host is a silhouette.

- Host: “Welcome to the Gauntlet! Ready for the “Reaper’s Breath”?”

- Panel 2: A wall of hot sauce bottles with names like “SUDDEN DEATH” and “COLON COLLAPSE.”

- Caption: SCOVILLE-BASED MARKETING. Row 2

- Panel 1: A graph showing Scoville levels skyrocketing over the years.

- Dr. Thorne: “To keep the signal “honest,” the heat must rise. You’re running to stand still.”

- Panel 2: Alex takes a bite. His face begins to melt into a smear of neon orange.

- Caption: THE POOLING EQUILIBRIUM. Row 3

- Panel 1: Two people at a table, both looking terrified of the wings in front of them, but neither will back down.

- Diner 1: “(Thinking) I hate this.”

- Diner 2: “(Thinking) I’m going to die.”

- Both: ““This is great, right?””

- Panel 2: Dr. Thorne stands between them, arms crossed.

- Dr. Thorne: “A Pareto-inferior equilibrium. You’re both suffering because you’re afraid of a condiment.”

Page 6

Row 1

- Dr. Thorne: “A Pareto-inferior equilibrium. You’re both suffering because you’re afraid of a condiment.”

- Panel 1: Alex is clutching the table. His eyes are streaming. He tries to speak, but only a jagged, neon-red shape comes out of his mouth.

- Alex: “I… I… [UNINTELLIGIBLE]”

- Panel 2: Dr. Thorne stands in a void of pure white.

- Dr. Thorne: “We’ve reached the point of Semiotic Collapse. The world is being unmade.” Row 2

- Panel 1: The restaurant, the cameras, the friends—all are dissolving into a sea of fire. Only Alex’s agonized face remains.

- Caption: PAIN ANNIHILATES LANGUAGE.

- Panel 2: Close up on Alex’s mouth. The word “AUTHENTIC” is shattering into pieces.

- Dr. Thorne: “The “Biological Real” has returned. It doesn’t care about your status or your “Thai Spicy” request.” Row 3

- Panel 1: Alex is curled in a fetal position on a floor of pure neon orange. He is silent.

- Dr. Thorne: “Beyond the last Scoville unit lies a silence no culture can metabolize.”

- Panel 2: Dr. Thorne walks away into the darkness, leaving the reader with a final look at the red chili pepper, now glowing like a dying star.

- Dr. Thorne: “We domesticate the absolute to feel alive. But the absolute… always wins in the end.”

- Caption: (Small, fading text) The body is a surface. The burn is the truth.

Auto-Fix Mode

Auto-applying: proceeding directly to visual generation.

Character: Dr. Aris Thorne

Cynical, intellectual, detached observer of human folly. Narrator/Philosopher. The guide for the reader through the ‘Semiotic Field’.

Character: The Subject (Alex)

Initially seeking social capital and ‘authenticity’, eventually reduced to primal biological reaction. Protagonist/Victim. The test subject for Dr. Thorne’s theories.

Narrative Generation Task

Overview

Narrative Generation

Subject: The Scoville Gauntlet: A Dramatization of the Spicy Food Semiotic Field

Configuration

- Target Word Count: 2500

- Structure: 3 acts, ~2 scenes per act

- Writing Style: literary

- Point of View: third person limited

- Tone: dramatic

- Detailed Descriptions: ✓

- Include Dialogue: ✓

- Internal Thoughts: ✓

Started: 2026-02-20 20:56:57

Progress

Phase 1: Narrative Analysis

Running base narrative reasoning analysis…

Cover Image

Prompt:

High-Level Outline

The Scoville Gauntlet

Premise: An exploration of the intersection of biological reality and social artifice through the lens of extreme capsaicin consumption, where a cultural critic and a lifestyle influencer battle to maintain their public personas under intense physical duress.

Estimated Word Count: 2496

Characters

Elias Thorne

Role: protagonist

Description: A lean, forty-something cultural critic with salt-and-pepper hair and a wardrobe of expensive, neutral-toned linens. He possesses a ‘curated’ face—one practiced in the art of the unimpressed smirk.

Traits: Intellectual, prideful, and deeply terrified of being seen as ‘common.’ He views the Gauntlet as a semiotic challenge—a test of his ability to maintain a sophisticated persona while his nervous system is under siege. He wants to prove that the mind can colonize the body’s pain.

Maya Vance

Role: antagonist / foil

Description: A twenty-four-year-old ‘stunt-lifestyle’ influencer. She is vibrant, wearing neon athletic gear that matches the studio lights. Her movements are twitchy, energetic, and calculated for maximum engagement.

Traits: Pragmatic, competitive, and hyper-aware of the ‘economy of attention.’ She views pain as a currency. Her goal is not to hide the suffering, but to weaponize it—to perform ‘authenticity’ more effectively than Elias performs ‘sophistication.’

Marcus “The Architect” Reed

Role: supporting / catalyst

Description: The host of the show. He wears a clinical white lab coat over a black turtleneck. He speaks in a soothing, low-frequency baritone that contrasts with the violence of the food.

Traits: Detached, observant, and slightly sadistic. He represents the ‘Industrialized Suffering’ of the media machine. He doesn’t care who wins; he only cares about the ‘spicy flush’ captured in 8K resolution.

Settings

gauntlet_studio

Description: A soundstage dominated by deep obsidian blacks and piercing neon magentas. The center table is a slab of polished white quartz, reflecting the high-intensity LED arrays overhead. Cameras are positioned at ‘predatory’ angles—extreme close-ups designed to capture sweat, pupil dilation, and the micro-tremors of the lips.

Atmosphere: Clinical, claustrophobic, and predatory. It feels less like a kitchen and more like a high-tech interrogation room or a biological laboratory.

Significance: It represents the ‘Panopticon of Performance,’ where every biological betrayal is recorded and commodified.

Act Structure

Act 1: The Illusion of Control

Purpose: To establish the ‘Sophistication Paradox’ and the initial social posturing between Elias and Maya.

Estimated Scenes: 2

Key Developments:

- The introduction of the first two wings

- Elias’s attempt to intellectualize the flavor profiles

- The first signs of physiological stress

Act 2: The Semiotic Collapse

Purpose: To dramatize the ‘Prisoner’s Dilemma’ of pain and the breakdown of the characters’ public personas.

Estimated Scenes: 2

Key Developments:

- The transition into the ‘danger zone’ of Scoville units

- The loss of verbal eloquence

- The physical ‘Red Queen Race’ where neither can afford to stop

Act 3: The Altar of the Scoville

Purpose: To reach the ‘Threshold of Semiotic Collapse’ and resolve the conflict through a moment of ‘Biological Honesty.’

Estimated Scenes: 2

Key Developments:

- The final wing consumption

- The climax of the physical pain

- The aftermath where the cameras stop rolling and personas dissolve

Status: ✅ Pass 1 Complete

Outline

The Scoville Gauntlet

Premise: An exploration of the intersection of biological reality and social artifice through the lens of extreme capsaicin consumption, where a cultural critic and a lifestyle influencer battle to maintain their public personas under intense physical duress.

Estimated Word Count: 2496

Total Scenes: 6

Detailed Scene Breakdown

Act 1: The Illusion of Control

Purpose: To establish the ‘Sophistication Paradox’ and the initial social posturing between Elias and Maya. Key Developments: The introduction of the first two wings; Elias’s attempt to intellectualize the flavor profiles; the first signs of physiological stress.

Scene 1: The Semiotic Appetizer

- Setting: gauntlet_studio

- Characters: Elias Thorne, Maya Vance, Marcus “The Architect” Reed

- Purpose: Introduce the characters, the setting, and the first wing (The Gateway). Establish the contrast between Elias’s intellectualism and Maya’s influencer persona.

- Emotional Arc: From confident posturing and professional detachment to the very first hint of physical vulnerability (the bead of sweat).

- Est. Words: 600

Key Events: { “introduction” : “Marcus Reed introduces the Gauntlet and the concept of culinary vs carnal.”, “character_posturing” : “Elias uses academic language (Baudrillard) while Maya focuses on her digital audience.”, “the_first_wing” : “The Gateway (50,000 Scoville) is served.”, “reaction” : “Elias dismisses the heat as ‘pedestrian’ while Maya embraces the ‘vibe’.”, “foreshadowing” : “A single bead of sweat appears on Elias’s hairline, signaling the start of the physical struggle.” }

Scene 2: The Terroir of Agony

- Setting: gauntlet_studio

- Characters: Elias Thorne, Maya Vance, Marcus “The Architect” Reed

- Purpose: Escalate the physical and psychological tension with the second wing (The Catalyst). Demonstrate the ‘Sophistication Paradox’.

- Emotional Arc: Increasing physical distress masked by intellectualization (Elias) and performative authenticity (Maya). The transition from control to the beginning of a breakdown.

- Est. Words: 750

Key Events: { “the_second_wing” : “Marcus introduces The Catalyst (250,000 Scoville).”, “intellectual_defense” : “Elias attempts to analyze the ‘neoliberal approach to spice’ while his voice falters.”, “social_friction” : “Maya mocks Elias’s physical state for her stream, highlighting his ‘beige’ appearance.”, “biological_betrayal” : “Marcus notes Elias’s dilated pupils; the body fights the mind’s narrative.”, “the_crack” : “Elias coughs and his eyes well up, breaking the clinical silence and the illusion of control.” }

Act 2: The Semiotic Collapse

Purpose: To dramatize the ‘Prisoner’s Dilemma’ of pain and the breakdown of the characters’ public personas.

Scene 1: The Lexical Erosion

- Setting: gauntlet_studio

- Characters: Elias Thorne, Maya Vance, Marcus “The Architect” Reed

- Purpose: To depict the transition from ‘spicy food’ to ‘chemical weapon’ and the first major victory of the body over the mind.

- Emotional Arc: From attempted sophistication and performance to raw biological panic and weaponized suffering.

- Est. Words: 1000

Key Events: { “1” : “Introduction of ‘The Obsidian Needle’ (850,000 SHU) and the shift in studio atmosphere to high-contrast violet.”, “2” : “Elias attempts an intellectual monologue but suffers a total loss of eloquence as the heat hits, failing to finish the word ‘palimpsest’.”, “3” : “Maya transitions from traditional performance to weaponizing her physical distress for the camera, claiming her suffering is ‘the real me’.”, “4” : “Marcus taunts Elias about the ‘colony in revolt,’ highlighting the shift from the semiotic to the somatic.” }

Scene 2: The Red Queen Race

- Setting: gauntlet_studio

- Characters: Elias Thorne, Maya Vance, Marcus “The Architect” Reed

- Purpose: To demonstrate the ‘Prisoner’s Dilemma’ of pain and the total collapse of persona into organism.

- Emotional Arc: From competitive dread to existential biological survival; mutual degradation and the death of the persona.

- Est. Words: 1200

Key Events: { “1” : “Introduction of ‘The Singularity’ (1.6 Million SHU) and the establishment of the ‘Prisoner’s Dilemma’ where neither participant wants to be the first to quit.”, “2” : “Maya experiences a total persona collapse, emitting a biological ‘error code’ instead of speech after taking a bite.”, “3” : “Elias’s pride forces him to continue despite his brain processing only the signal of ‘Fire’, losing all ability to formulate industrial critiques.”, “4” : “Marcus observes the ‘birth of the organism’ as the characters reach a physical and psychological stalemate, staring each other down over the milk.” }

Act 3: The Altar of the Scoville

Purpose: To reach the ‘Threshold of Semiotic Collapse’ and resolve the conflict through a moment of ‘Biological Honesty.’

Scene 1: The Singularity

- Setting: gauntlet_studio

- Characters: Elias Thorne, Maya Vance, Marcus “The Architect” Reed

- Purpose: This scene depicts the consumption of the final wing, representing the total breakdown of the characters’ carefully constructed personas.

- Emotional Arc: The characters transition from performative sophistication and calculated energy to a state of primal, mammalian dread and total chemical emergency.

- Est. Words: 750

Key Events: { “introduction” : “Marcus introduces ‘The Singularity’, a wing coated in six million Scoville units of capsaicin extract.”, “consumption” : “Elias and Maya consume the final wing, leading to an immediate breakdown of their personas.”, “collapse” : “The characters experience a total semiotic collapse, where language and branding dissolve into raw biological reaction.” }

Scene 2: The Cooling Down

- Setting: gauntlet_studio

- Characters: Elias Thorne, Maya Vance, Marcus “The Architect” Reed

- Purpose: The aftermath of the physical pain where artifice is stripped away and a moment of genuine, unmediated human connection occurs between the two rivals.

- Emotional Arc: A transition from intense physical suffering to a quiet, shared vulnerability and genuine human connection.

- Est. Words: 500

Key Events: { “production_ends” : “Marcus calls ‘cut’ and the theatrical studio lights are replaced by soft, mundane amber lighting.”, “recovery” : “Elias and Maya begin to recover, speaking to each other without their usual masks of sophistication or engagement.”, “connection” : “The rivals find common ground in the shared trauma of their experience, achieving ‘Biological Honesty.’”, “conclusion” : “The characters are led off-set, leaving behind a messy studio that reflects the end of the performance.” }

Status: ✅ Complete

Setting: gauntlet_studio

Prompt:

Character: Elias Thorne

Prompt:

Character: Maya Vance

Prompt:

Character: Marcus “The Architect” Reed

Prompt:

## The Semiotic Appetizer

Act 1, Scene 1

Setting: gauntlet_studio

Characters: Elias Thorne, Maya Vance, Marcus “The Architect” Reed

The studio was a vacuum of polished obsidian and surgical steel, a sterile stage bathed in the unforgiving halo of ring lights. At the center sat a triangular table, its surface so reflective that Elias Thorne could see the distorted underside of his own jaw. Three high-definition cameras tracked him with the silent, predatory hunger of deep-sea creatures.

To his left, Maya Vance performed a ritual of digital vanity. She tilted her head, checking her reflection in the lens of Camera Two, smoothing a stray hair into her honey-blonde blowout. She wasn’t looking at the room; she was looking at the imaginary millions she carried in her pocket like a digital rosary.

“Welcome to the Scoville Gauntlet,” Marcus Reed announced. His baritone was cultivated and clinical, a scalpel of sound. Known as ‘The Architect,’ Marcus stood at the head of the table, his charcoal suit as sharp as the lighting. “Tonight, we move beyond the artifice of the palate. We are not here for the culinary, but for the carnal. We are here to see what remains of the persona when biology takes over.”

Elias offered a thin, practiced smile. “A fascinating premise, Marcus. Though I suspect your ‘carnal’ is merely another layer of performance. We’re participating in a Baudrillardian hyperreality—the pain is real, yes, but the display of pain is the only currency that matters here.”

Maya let out a melodic, hollow laugh. “Elias, babe, you’re overthinking it. It’s just a vibe. People want to see us be real. They want the raw, unedited journey. Right, guys?” She winked at her primary camera, her thumb hovering over an invisible ‘post’ button.

“Then let the journey begin,” Marcus said. A masked assistant placed two white porcelain plates on the table. On each sat a single chicken wing, coated in a deceptive, sunset-orange glaze.

“The Gateway,” Marcus declared. “Thai Bird’s Eye chilies with a fermented habanero base. Fifty thousand Scoville units. A mere greeting.”

Elias picked up the wing with silver tongs, refusing to soil his fingers. He examined it with the detached curiosity of a pathologist. “Fifty thousand. Pedestrian. The heat equivalent of a brisk autumn breeze. A minor irritant to the mucous membranes, easily suppressed by the intellect.”

Maya used her manicured fingers, posing as the sauce glistened under the LEDs. “It smells… spicy-sweet. Like a bad breakup.” She took a dainty, deliberate bite. Her eyes widened for the lens. “Oh, wow. Okay. That’s a kick. It’s like a sparkler going off on my tongue.”

Elias took a bite. The heat was immediate—a sharp, needle-like prickling across his soft palate. He chewed slowly, maintaining a mask of scholarly indifference as the warmth slid down his esophagus like a swallowed coal.

“The capsaicin binds to the TRPV1 receptors,” Elias said, his voice steady despite a tightening throat. “The brain receives a signal of thermal abrasion, yet there is no tissue damage. It is the ultimate lie of the nervous system.”

“Is it a lie if it hurts?” Maya asked, her breath hitching. Her cheeks were flushing a cinematic pink. “I feel so… awake. My heart is actually racing.”

“Adrenaline,” Elias dismissed, though his own pulse throbbed against his collar. He reached for his water, then stopped. He would not be the first to break.

He looked at Marcus, ready to deliver another critique, but the words snagged. A single, microscopic bead of moisture had formed at the center of Elias’s hairline. A salt-rimmed traitor. He felt it—a cold prickle against his skin that felt like a mountain of ice in the desert of his burning mouth. The Gateway was open, and the biological reality was already eroding the social artifice.

Word Count: 610

Key Moments:

- Marcus Reed sets the philosophical and physical stakes of the Gauntlet, framing it as a battle between persona and biology.

- Elias attempts to intellectualize the experience using academic theory (Baudrillard), while Maya frames it as an ‘authentic’ moment for her digital brand.

- The first wing, ‘The Gateway’ (50,000 SHU), is consumed, serving as the baseline for the physical escalation to come.

- Despite his verbal dismissal of the heat, Elias experiences the first involuntary physical symptom—a bead of sweat—signaling the beginning of his loss of control.

Character States:

- Elias Thorne: Emotionally arrogant and intellectually detached; physically, his body is beginning to react to the capsaicin despite his mental resistance (the bead of sweat).

- Maya Vance: Emotionally performative and focused on her ‘brand’; physically, she is experiencing a ‘high’ from the adrenaline and heat, leaning into the sensation for the camera.

- Marcus Reed: Calm, authoritative, and observant; he remains the detached ‘Architect’ overseeing the experiment.

Status: ✅ Complete

Act 1, Scene 1 Image

Prompt:

## The Terroir of Agony

Act 1, Scene 2

Setting: gauntlet_studio

Characters: Elias Thorne, Maya Vance, Marcus “The Architect” Reed

The bead of sweat on Elias Thorne’s forehead was no longer a solitary scout; it had been joined by a battalion. The studio lights, once merely bright, now functioned like heat lamps in a vivarium. Across the obsidian table, Marcus “The Architect” Reed sat with the stillness of a gargoyle, his gloved hands hovering over a tray of porcelain ramekins.

“The Gateway was a courtesy,” Marcus said, his voice a low, resonant cello. “A handshake. Now, we move to the conversation. This is ‘The Catalyst.’ Two hundred and fifty thousand Scoville units. A blend of Habanero and Scotch Bonnet, fortified with a distilled oleoresin.”

He placed the second wing before them. It was a deep, bruised orange, glistening with an oil that seemed to vibrate under the LEDs.

Maya Vance didn’t hesitate. She adjusted her ring light, her smile flashing with the practiced precision of a predator. “Look at that color, guys,” she whispered to her phone, her voice a breathy, curated intimacy. “It’s like a sunset in a bottle. Or a warning. Elias, you look a little… muted. Are we losing our color?”

Elias felt the heat from the first wing radiating in his gut, a slow-blooming nebula of discomfort. He adjusted his glasses, which were beginning to slide down the bridge of his nose.

“Color is a bourgeois preoccupation, Maya,” Elias said, though his voice lacked its usual resonance. It sounded thin, like parchment being stretched. “What we’re seeing here is the neoliberal approach to spice. It’s not about flavor; it’s about the performative endurance of a manufactured crisis. We’ve commodified the biological fight-or-flight response into a consumable spectacle.”

He picked up the wing. His fingers betrayed a micro-tremor he hoped the cameras wouldn’t catch. He took a bite.

The heat was immediate and vertical. It didn’t wash over his tongue; it pierced it. It was a chemical needle, threading through his mucous membranes and stitching his throat shut. The Catalyst lived up to its name, igniting a chain reaction that turned his saliva into molten lead.

“Interesting,” Marcus noted, leaning forward. He wasn’t looking at the wings; he was studying Elias’s eyes. “The Sophistication Paradox in real-time. The more the mind attempts to categorize the pain, the more the body rebels against the categorization. Elias, your pupils are blown. Mydriasis. Your sympathetic nervous system has decided that Baudrillard can’t save you from a capsaicin burn.”

Maya laughed, a sharp, bright sound. She had taken her bite and was leaning into the burn, her face flushed a vibrant, healthy pink. “He’s turning beige, Marcus. Is beige a color? He looks like a library book that’s been left in the sun.” She turned her camera toward Elias, capturing the sheen of moisture on his upper lip. “Elias, tell the fans about the… what was it? The manufactured crisis? You look like you’re having a real one.”

Elias tried to retort. He had a brilliant point about the intersection of sensory overload and the erosion of the ego, but the words were trapped behind a wall of fire. His throat felt as though it had been lined with crushed glass. The “terroir” Marcus had promised was a landscape of scorched earth.

He swallowed, and the movement felt like a betrayal. The heat descended into his esophagus, a slow-moving lava flow.

“The… the irony,” Elias managed, his voice cracking—a jagged sound that broke the clinical silence of the room. “The irony is that the… the body’s insistence on reality… is the only thing… that isn’t… simulated.”

A sudden, violent tick developed in his left eyelid. His vision blurred as his tear ducts, sensing the chemical assault, began to overcompensate. A single, heavy tear escaped, carving a path through the fine dusting of translucent powder on his cheek.

Then came the cough.

It was a dry, hacking sound—the sound of a man trying to expel his own lungs. Elias clutched the edge of the table, his knuckles white. The intellectual defense had failed. The fortress of his vocabulary had been breached by a pepper.

“The crack,” Marcus whispered, almost to himself. He looked satisfied, like a scientist watching a crystal lattice finally shatter under pressure. “The social artifice is melting, Elias. Tell me, in this moment, does the ‘neoliberal approach’ matter? Or is there only the burn?”

Elias couldn’t answer. He reached for his glass of water, his hand shaking so violently that the ice clinked a frantic rhythm against the glass. He stopped just short of drinking, his pride a dying ember in the furnace of his mouth. He looked at Maya, who was grinning, her eyes wide and hungry for the content of his collapse.

He forced himself to set the glass down. His eyes were bloodshot, swimming in involuntary salt water, but he stared at Marcus with a raw, primal defiance.

The Catalyst had done its work. The conversation had truly begun.

Word Count: 813

Key Moments:

- Marcus escalates the heat to 250,000 SHU with ‘The Catalyst’, moving from a ‘handshake’ to a ‘conversation’.

- Elias attempts to frame the pain as a neoliberal construct, but his physical symptoms (dilated pupils, trembling) betray his mental detachment.

- Elias suffers a coughing fit and an involuntary tear, marking the first major crack in his composed, academic persona while Maya weaponizes his distress for her audience.

Character States:

- Elias Thorne: Physically distressed and losing control; his throat is ‘scorched earth,’ and his eyes are tearing up. Emotionally, he is desperate to maintain his intellectual superiority but is failing.

- Maya Vance: Physically flushed and ‘high’ on the adrenaline; she is leaning into the pain to appear ‘authentic’ and is thriving on Elias’s visible struggle.

- Marcus Reed: Calm, clinical, and observant; he is pleased to see the ‘Sophistication Paradox’ taking effect and the breakdown of Elias’s social mask.

Status: ✅ Complete

Act 1, Scene 2 Image

Prompt:

## The Lexical Erosion

Act 2, Scene 1

Setting: gauntlet_studio

Characters: Elias Thorne, Maya Vance, Marcus “The Architect” Reed

The studio lights pivoted with a hydraulic hiss. The inviting amber of the previous round vanished, replaced by a bruised, high-contrast violet that turned the sweat on Elias’s brow into beads of cold mercury. The air conditioning hummed—a low-frequency vibration that didn’t cool the room so much as rattle the marrow of his teeth.

Marcus Reed, “The Architect,” sat behind the obsidian table like a judge presiding over a neon purgatory. Between them lay the next offering: a single chicken wing coated in a sauce so dark it seemed to absorb the violet light, a matte void on a white ceramic plate.

“The Obsidian Needle,” Marcus announced, his voice a smooth, terrifying baritone. “Eight hundred and fifty thousand Scoville Heat Units. We have moved past the ‘Catalyst.’ We are now entering the realm of the chemical weapon. This is no longer a culinary experience, Elias. It is a biological intervention.”

Elias Thorne stared at the wing. His mouth was already a ruin, a landscape of scorched earth where his taste buds used to reside. His pulse thrummed in his ears, a frantic, syncopated rhythm. He felt the phantom weight of his reputation—decades of sharp-tongued critiques and the effortless deconstruction of culture—pressing down on his shoulders. He needed to speak. He needed to colonize this pain with language before it colonized him.

“It’s… a fascinating escalation,” Elias said, his voice cracking like dry parchment. He cleared his throat, the sound wet and jagged. “The transition from the gustatory to the purely… purely somatic. It’s a classic postmodern maneuver. We are stripping away the signifier of ‘food’ to reveal the raw, unmediated… the raw…”

He reached for the wing. His fingers trembled, a fine-motor betrayal he couldn’t suppress. He took a bite.

For three seconds, there was nothing but the metallic tang of vinegar. Then, the Needle struck.

It wasn’t heat. Heat was a campfire; heat was a summer day. This was a localized tectonic shift. It felt as though a thousand microscopic glass shards had been dipped in battery acid and driven into the soft tissue of his throat. His sinuses didn’t just open; they screamed.

“The beauty of this,” Elias gasped, his eyes bulging, “is the way it… it functions as a… a palim—”

The word died. Palimpsest. He wanted to say palimpsest—to describe how the pain was overwriting his previous sensory experiences. But the ‘p’ was a puff of hot air, and the ‘l’ was a strangled sob. His tongue had become a foreign object, a heavy, swollen slug that refused to obey the commands of his prefrontal cortex. He gripped the edge of the table, his knuckles white. The violet light pulsed in time with the throbbing in his carotid artery.

Beside him, Maya Vance was undergoing a different kind of transformation.

She wasn’t fighting the erosion; she was curating it. Tears streamed down her face, carving tracks through her high-definition foundation, but she didn’t wipe them away. She leaned into the camera, her breath coming in ragged, shallow hitches. Her eyes, bloodshot and shimmering, were fixed on the lens with a terrifying, predatory intensity.

“Do you see this?” she whispered, her voice a raspy ghost of its usual melodic lilt. She held up her shaking hand, the Obsidian Needle held like a grim trophy. “This isn’t a filter. This isn’t a script. This is… this is the real me. I’m burning. I’m literally burning for you guys.”

She took another bite, a deliberate act of self-immolation. She winced, a spasm of genuine agony crossing her face, but she immediately smoothed it into a look of tragic ecstasy.

“Maya,” Marcus said, leaning forward, “you’re weaponizing your own distress. It’s brilliant. You’ve turned a biological crisis into a brand identity.”

“It’s… authenticity,” Maya choked out. A string of saliva escaped the corner of her mouth, but she didn’t flinch. The engagement metrics in her head were surely skyrocketing. “Pain is the only thing… the only thing they can’t… fake.”

Marcus turned his gaze back to Elias, who was currently hunched over, his face a deep, alarming shade of plum. Elias was trying to breathe through his nose, but his lungs felt like they were filled with hot sand.

“How’s the monologue coming, Elias?” Marcus asked, his tone dripping with clinical curiosity. “You look like a man who has lost his dictionary.”

Elias looked up. He tried to summon a scathing retort, a witty observation about the banality of Marcus’s sadism. He opened his mouth, and for a moment, the ghost of a sentence formed in his mind: The architectural cruelty of this environment suggests a—

“Guh,” Elias said.

That was it. A guttural, primal sound. The “colony” of his body had officially declared independence from the “governor” of his mind. His nervous system was screaming so loudly that the intellect had been evicted.

“The colony is in revolt,” Marcus said, echoing Elias’s internal thought with haunting accuracy. “The semiotic has been conquered by the somatic. You wanted to talk about the ‘social artifice’ of the Gauntlet, Elias. But right now, you aren’t a critic. You aren’t a scholar. You’re just a collection of nerve endings trying not to vomit.”

Elias felt a tear escape his left eye. It wasn’t a tear of sadness; it was a tear of pure, chemical exhaustion. He looked at the glass of milk sitting just out of reach. It looked like a holy relic, a white beacon of salvation. His pride, which had felt like an iron suit of armor only ten minutes ago, was now a lead weight dragging him into the abyss.

Maya let out a sharp, jagged laugh that turned into a cough. “He’s… he’s broken,” she wheezed, pointing a trembling finger at Elias. She looked at the camera, her expression one of manic triumph. “The Great Elias Thorne… out of words. I guess… I guess I’m the only one… still talking.”

She was right. She was winning because she had accepted the degradation. She had traded her dignity for “content,” while Elias was still trying to trade his pain for “meaning.” And in the violet glow of the Obsidian Needle, meaning was a currency that no longer held any value.

Elias reached out. His hand hovered over the milk. He looked at Marcus, whose eyes were cold and expectant. He looked at Maya, who was filming his defeat with a predatory grin.

He didn’t drink. Not yet. But the silence where his words used to be was the loudest sound in the room.

“Next round,” Marcus said, his voice a death knell. “We go to one point two million. Let’s see if there’s anything left of you to burn.”

Word Count: 1109

Key Moments:

- The Introduction of the Obsidian Needle: The stakes are raised to 850,000 SHU, and the studio environment shifts to a hostile, high-contrast violet, signaling the move from ‘food’ to ‘chemical weapon’.

- The Lexical Collapse: Elias attempts to maintain his intellectual superiority through a monologue but suffers a total breakdown of language, failing to complete the word ‘palimpsest’ as his biology overrides his intellect.

- Maya’s Weaponized Suffering: Maya leans into her physical distress, using her tears and pain to claim a new level of ‘authenticity’ for her brand, effectively winning the social battle by embracing the biological one.

- The Architect’s Taunt: Marcus highlights the ‘colony in revolt,’ mocking Elias for losing his vocabulary and pointing out that the body has officially conquered the mind.

Character States:

- Elias Thorne: Physically shattered and intellectually silenced. He is in a state of ‘lexical erosion,’ where his primary tool—language—has failed him. He is hovering on the edge of total surrender.

- Maya Vance: Physically in pain but emotionally empowered. She has successfully commodified her suffering and feels a sense of triumph over Elias’s collapse.

- Marcus Reed: Calm, observant, and increasingly dominant. He is enjoying the ‘Sophistication Paradox’ as he watches the high-level thinkers and performers reduced to primal reactions.

Status: ✅ Complete

Act 2, Scene 1 Image

Prompt:

## The Red Queen Race

Act 2, Scene 2

Setting: gauntlet_studio

Characters: Elias Thorne, Maya Vance, Marcus “The Architect” Reed

The studio’s violet light had curdled into a bruised, ultraviolet rot, turning the white porcelain spoons into glowing, irradiated shards. The air was no longer oxygen; it was a saturated aerosol of pulverized peppers—a fine mist of capsaicin that clung to the soft tissue of the throat like a threat.

Marcus “The Architect” Reed sat in the center of the gloom, a sharp, ink-black silhouette against a wall of glowing monitors. Between Elias and Maya sat a single obsidian ramekin. Inside was a substance so dark it seemed to exert its own gravity—a viscous, maroon sludge that smelled less like food and more like an electrical fire in a chemical plant.

“This,” Marcus said, his voice dropping into a reverent, clinical register, “is The Singularity. One point six million Scoville Heat Units. We have moved past the threshold of culinary experience. We are now in the realm of neuro-chemical warfare.” He leaned forward, his eyes unblinking in the harsh light. “Your bodies will tell you that you are dying. Your brains will attempt to shut down non-essential systems to preserve the core. The question is: which of you is more than just a collection of panicked nerves?”

Elias Thorne stared at the sludge. His hands were trembling—a fine, high-frequency vibration he couldn’t suppress. His throat felt as though it had been lined with fiberglass. He wanted to speak, to offer a pithy observation about the fetishization of extremity in late-stage capitalism, but the words felt like dry sand in his mouth. He looked at Maya.

Maya Vance was no longer the polished avatar of lifestyle perfection. Her mascara had dissolved into dark, jagged canyons down her cheeks. Her breathing was shallow, ragged, the hyperventilation of a prey animal. Yet, she held her phone with a white-knuckled, skeletal grip. The “Live” icon was a pulsing red eye, a digital witness to her unraveling.