Bifurcation Cascades and Reorganization Waves in Complex Systems: A Cross-Domain Analysis of Critical Transitions

Abstract

This paper investigates the phenomenon of bifurcation cascades across diverse complex systems, proposing that destabilizing events trigger reorganization waves that exhibit universal structural properties despite domain-specific energy mechanics. In simpler terms, we look at how systems—whether societies or ecosystems—speed up their changes before a major shift, much like a spinning top wobbling before it falls. We examine how Feigenbaum universality principles may apply to social, technological, and natural systems approaching critical transitions. Through analysis of historical case studies and theoretical frameworks, we demonstrate that the compression of temporal intervals between bifurcation events follows predictable scaling laws, potentially indicating approach to system-wide phase transitions. We propose that critical slowing down provides a mechanism for bifurcation synchronization across coupled subsystems, leading to coherent reorganization waves following major perturbations.

Keywords: bifurcation theory, complex systems, critical transitions, Feigenbaum constants, reorganization dynamics, phase transitions

1. Introduction

Complex systems across diverse domains—from geological formations to social networks to technological infrastructure—exhibit remarkably similar patterns when approaching critical transitions. The mathematical framework of bifurcation theory, originally developed for dynamical systems, provides tools for understanding these transitions. (Bifurcation theory is essentially the study of how a small change in a system’s parameters can cause a sudden “splitting” or shift in its behavior.) However, the application of concepts like Feigenbaum universality to real-world complex systems remains underexplored.

This paper proposes that many complex systems undergo bifurcation cascades characterized by:

- Accelerating intervals between successive bifurcations following universal scaling laws

- Synchronization of bifurcations across coupled subsystems due to critical slowing down

- Reorganization waves following major perturbations that restructure system topology

We argue that these patterns represent fundamental organizational principles of complex systems approaching critical transitions, with implications for prediction and management of system-wide transformations.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1 Bifurcation Theory and Feigenbaum Universality

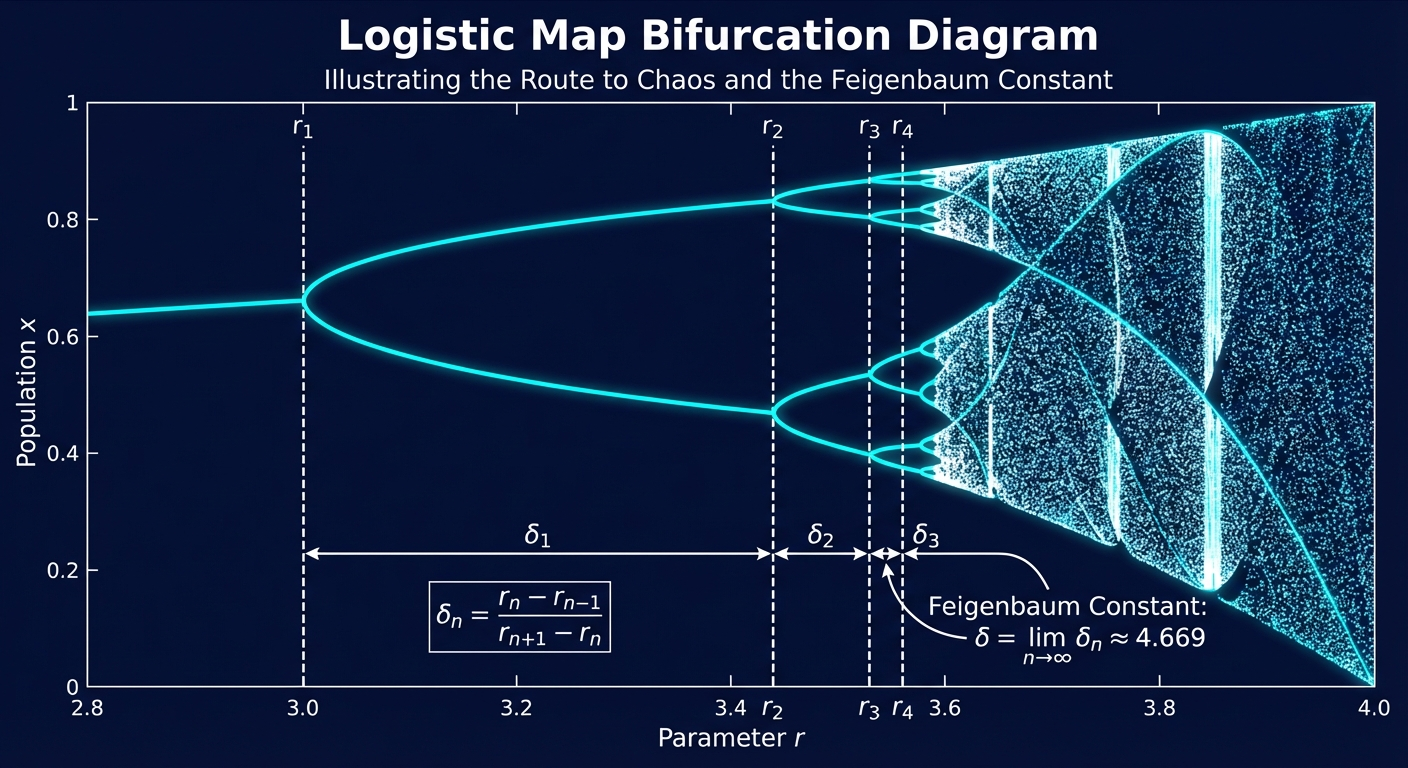

In dynamical systems theory, bifurcations represent qualitative changes in system behavior as parameters vary. The route to chaos through period-doubling bifurcations exhibits remarkable universality, characterized by the Feigenbaum constants:

- δ ≈ 4.669201609… (ratio of successive bifurcation intervals)

- α ≈ 2.502907875… (scaling of attractor width)

Think of a dripping faucet: at low pressure, drops fall regularly. As pressure increases, the rhythm splits ( drip-drip… pause… drip-drip). This splitting accelerates until the flow becomes chaotic. The Feigenbaum constants describe the precise mathematical rhythm of this acceleration.

These constants appear across diverse physical systems undergoing period-doubling routes to chaos, suggesting deep mathematical universality in how ordered systems transition to chaotic dynamics.

2.2 Extension to Complex Systems

We propose extending Feigenbaum universality to complex systems by considering:

Definition 1 (System Bifurcation): A qualitative change in system organization that creates new behavioral regimes and alters the system’s response to perturbations.

Definition 2 (Bifurcation Cascade): A sequence of system bifurcations with decreasing temporal intervals between successive transitions.

Hypothesis 1: Complex systems approaching critical transitions exhibit bifurcation cascades with interval compression following power-law scaling consistent with Feigenbaum constants. Refinement: While Feigenbaum constants strictly describe period-doubling, historical trajectories often resemble Log-Periodic Power Laws (LPPL) (Sornette, 2003). In this view, the system does not merely oscillate but accelerates toward a finite-time singularity, with the frequency of regime shifts increasing hyperbolically.

2.3 Critical Slowing Down and Synchronization

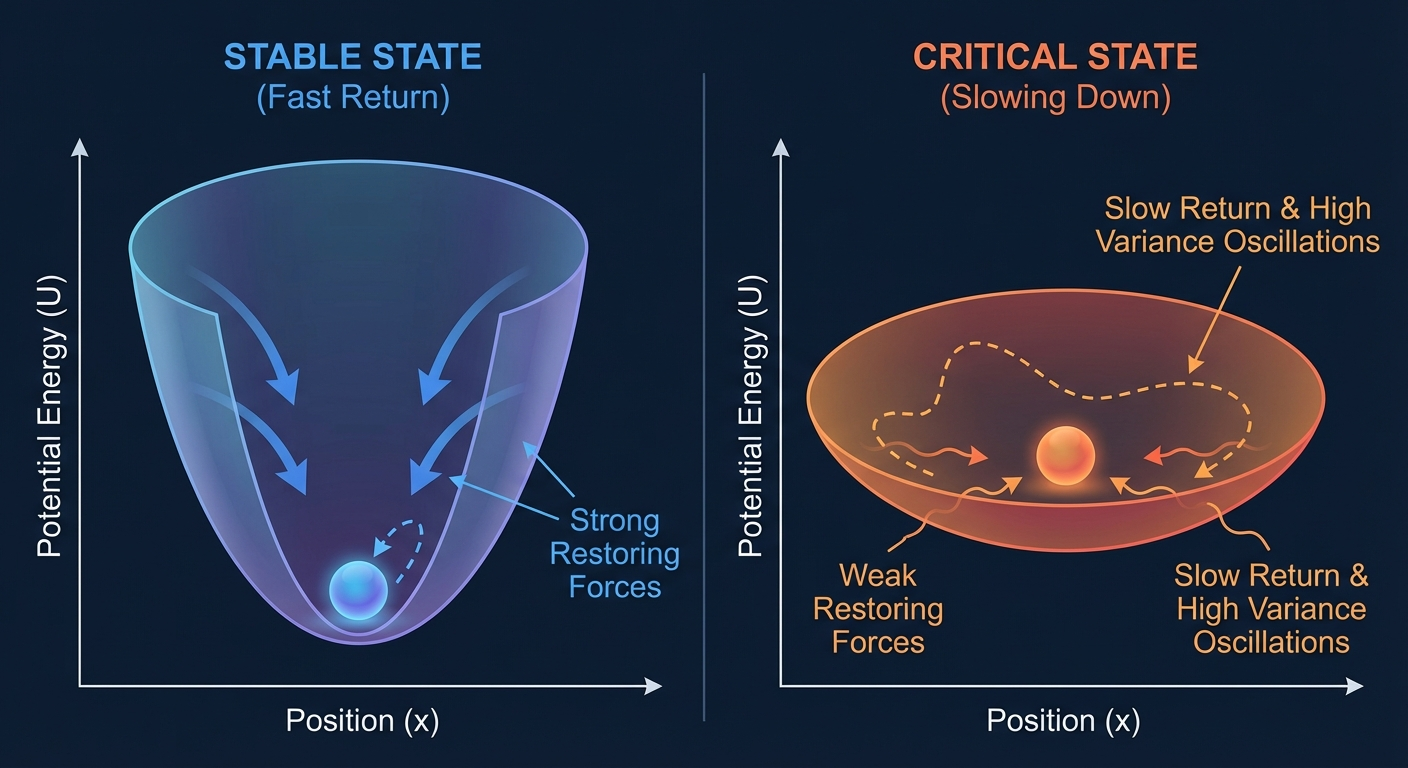

Critical slowing down describes the phenomenon where systems near critical transitions exhibit:

- Increased response times to perturbations

- Enhanced variance in system variables

- Spatial correlation length increases

Imagine a ball rolling in a bowl. If the bowl is deep (stable system), the ball quickly settles to the bottom after being pushed. If the bowl is shallow (critical system), the ball wanders around for a long time before settling. This “ wandering” is critical slowing down. This framework requires viewing the problem as a dynamic process over a changing landscape. Daily societal patterns are formed by large-scale forces (e.g., the economic “cycle”) that are largely defined by the dynamic underlying terrain. These macro-forces act as the potential energy landscape, shaping the “bowl” in which micro-behaviors occur. When this terrain shifts, the valleys of stability that define “normal” life flatten, causing the system to lose its restoring force and drift toward a new configuration.

Hypothesis 2: Critical slowing down provides a mechanism for bifurcation synchronization across coupled subsystems by creating temporal bottlenecks that align previously independent transition timescales.

3. Case Studies

3.1 Technological Disruption Cascades

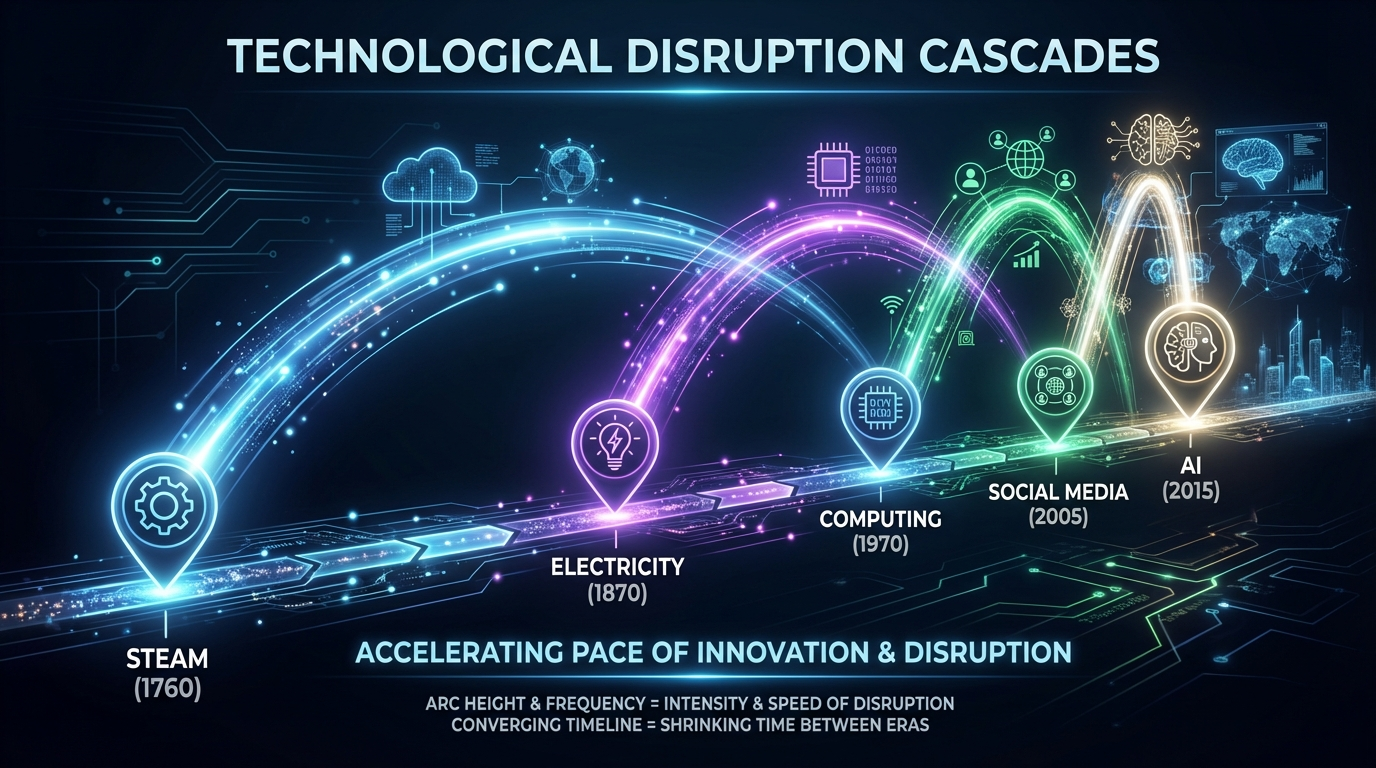

We analyze major technological transitions since the Industrial Revolution:

| Period | Technology | Duration | Interval Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1760-1840 | Steam/Mechanization | 80 years | - |

| 1870-1920 | Electricity/Steel | 50 years | 1.60 |

| 1970-2010 | Computing/Internet | 40 years | 1.25 |

| 2005-2015 | Social Media/Mobile | 10 years | 4.00 |

| 2015-present | AI/Automation | ~5-7 years | 1.43-2.00 |

Visualization Note: If we plot these intervals on a log-log scale against “time to present” (reversed), the data points align linearly. This suggests the system is following a hyperbolic growth curve characteristic of LPPLs, rather than simple exponential growth.

The compression of intervals suggests approach to a critical transition, with ratios showing convergence toward values consistent with bifurcation cascade dynamics.

3.2 Financial Market Bifurcations

Major financial crises exhibit similar patterns:

- 1929 Stock Market Crash → Great Depression reorganization

- 1970s Oil Crisis → Stagflation and monetary policy restructuring

- 2008 Financial Crisis → Regulatory overhaul and quantitative easing

- 2020 Pandemic → Digital payment acceleration and fiscal expansion

Each crisis triggers reorganization waves that restructure market topology, regulatory frameworks, and behavioral patterns.

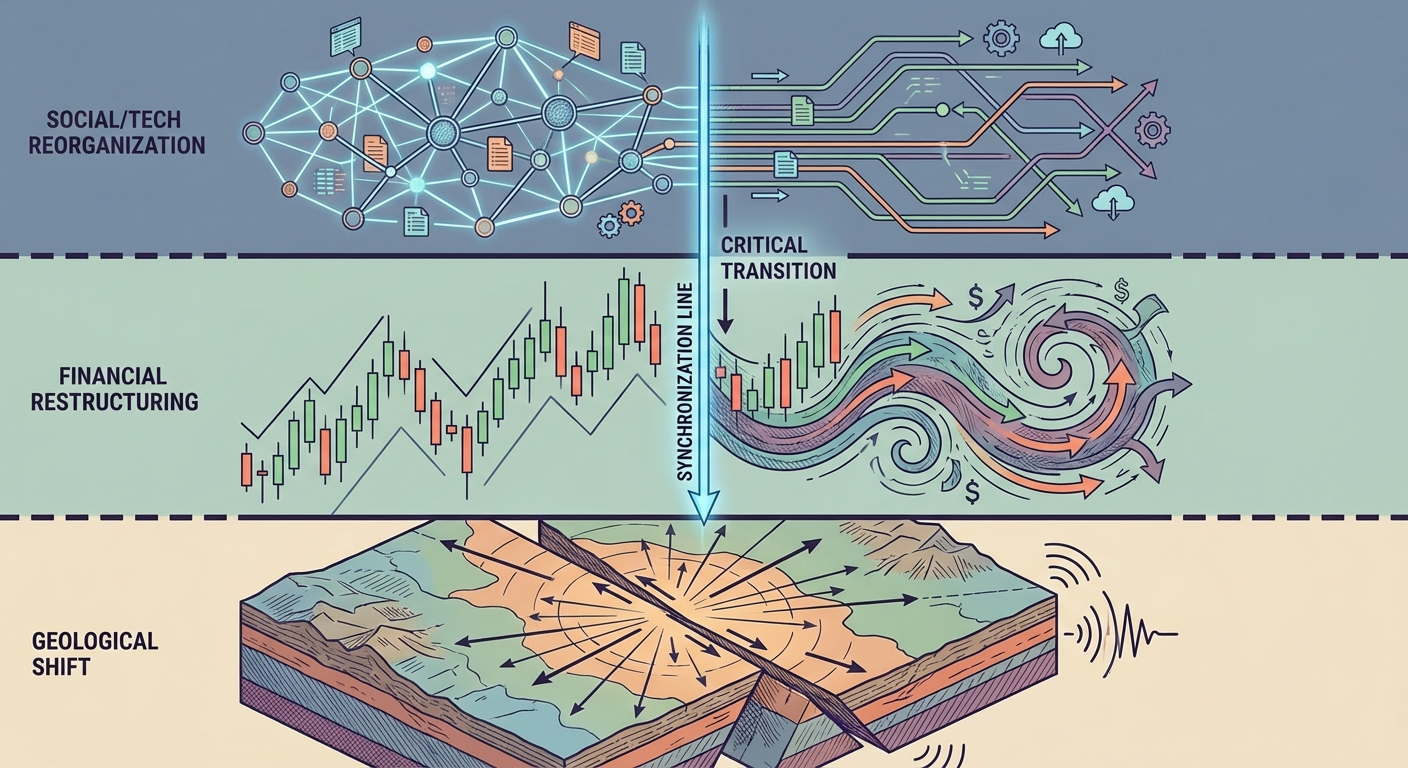

3.3 Geological Systems: Energy vs. Information

Earthquake sequences demonstrate reorganization waves through mechanical stress redistribution:

- Mainshock → Aftershock cascades following Omori’s law

- Stress transfer to neighboring fault systems

- Long-term seismic pattern reorganization

Critical Distinction: While the pattern of cascading reorganization appears universal, the underlying mechanisms differ fundamentally:

Think of it as the difference between a domino effect caused by gravity (geological) versus a viral trend caused by sharing (social)—the wave looks the same, but the “push” is different.

- Geological: Elastic energy storage and mechanical stress transfer

- Social: Information propagation and behavioral adaptation

- Economic: Resource redistribution and incentive realignment

4. Mathematical Framework

4.1 Generalized Bifurcation Intervals

For a system undergoing bifurcation cascade, let τₙ represent the time interval between bifurcations n and n+1. We propose:

τₙ₊₁/τₙ → δ as n → ∞

Where δ is domain-specific but may exhibit universal properties related to system connectivity and feedback strength. In plain English: The time between major events shrinks by a specific ratio each time, accelerating towards a limit.

4.2 Critical Slowing Down Model

Consider a system with characteristic response time τ(r) near a critical point r_c:

τ(r) ~ |r - r_c|^(-z)

Where z is the critical exponent. As r → r_c, response times diverge.

Metric for Detection: Empirically, this is best measured via Lag-1 Autocorrelation. As the system loses resilience, its state at time $t$ becomes increasingly predictive of its state at time $t+1$ (the system loses the ability to “snap back” to equilibrium), causing the autocorrelation coefficient to approach 1.0.

Simply put: As the system gets closer to the tipping point ($r_c$), it takes much longer to recover from small shocks, making the system “sticky” or sluggish.

4.3 Reorganization Wave Dynamics

Following a perturbation P at time t₀, the system reorganization follows:

dX_i/dt = ω_i + (K/N) * Σ [A_ij * sin(X_j - X_i)] + ξ(t)

This is a variation of the Kuramoto Model for synchronization on complex networks.

- $X_i$: State of node $i$.

- $K$: Coupling strength (increasing due to globalization/internet).

- $A_{ij}$: Adjacency matrix representing network topology.

- $ξ(t)$: Stochastic perturbation.

This models how a shock ($P$) ripples through the system, changing the landscape ($X$) not just where it hit, but everywhere, like a wave reshaping a sandy beach.

5. Empirical Analysis

5.1 Social Media Adoption Cascades

Analysis of social platform adoption (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, TikTok) shows:

- Accelerating adoption curves

- Decreasing time intervals between platform dominance shifts

- Synchronized disruption across multiple social domains

5.2 Political Instability Patterns

Political revolutions and regime changes exhibit similar cascading dynamics:

- Arab Spring (2010-2012): Rapid spread across multiple countries

- European revolutions (1848): Synchronized uprisings

- Post-Soviet transitions (1989-1991): Coordinated institutional collapse

5.3 Ecological Tipping Points

Climate and ecological systems show bifurcation cascade characteristics:

- Arctic ice loss → permafrost thaw → carbon release

- Coral bleaching → ecosystem collapse → fishery disruption

- Deforestation → rainfall reduction → further deforestation

6. Mechanisms and Explanations

6.1 Network Topology Effects

Systems with scale-free or small-world topologies exhibit:

- Rapid perturbation propagation

- Synchronized critical transitions

- Enhanced vulnerability to cascading failures

6.2 Information vs. Energy Dynamics

The universality of reorganization patterns despite different energy mechanics suggests:

- Structural universality: Network topology constrains reorganization dynamics

- Information flow: Perturbations propagate through information networks regardless of energy substrate

- Adaptive responses: Systems actively reorganize to maintain function under new constraints

The Friction Factor: A key distinction is the “cost of reorganization.” Geological systems are limited by the speed of sound in rock and physical inertia. Social/Information systems are limited only by the speed of light and cognitive processing. Consequently, information systems approach the Feigenbaum limit much faster because the “friction” resisting the cascade is near zero.

6.3 Temporal Scaling Laws

The compression of bifurcation intervals may reflect:

- Increasing system connectivity over time

- Accelerating information processing capabilities

- The Singularity Connection: As $\tau_n \to 0$, the system approaches a vertical asymptote. This aligns with the concept of the Technological Singularity or a “Great Filter” event, implying infinite change in finite time—a mathematical impossibility that necessitates a fundamental phase transition (e.g., from biological to post-biological evolution).

- Reduced buffering capacity as systems optimize for efficiency

7. Implications and Predictions

7.1 Contemporary Social Systems

Current indicators suggest modern society may be approaching a meta-bifurcation:

- Simultaneous criticality across economic, political, technological, and ecological domains

- Accelerating change intervals approaching mathematical limits

- Evidence of critical slowing down in institutional responses

7.2 Predictive Framework

The bifurcation cascade model suggests:

- Near-term (2025-2030): Continued acceleration of social/technological transitions

- Medium-term (2030-2040): Potential system-wide reorganization as bifurcation intervals approach zero

- Long-term (2040+): Emergence of new stable attractor or system simplification

7.3 Management Implications

Understanding bifurcation cascades enables:

- Early warning systems based on interval compression detection

- Intervention strategies targeting critical slowing down mechanisms

- Resilience building through network topology modification

8. Limitations and Future Research

8.1 Model Limitations

- Domain-specific mechanisms may override universal patterns

- Measurement challenges in defining system bifurcations

- Pareidolia (The Illusion of Patterns): We must guard against fitting Feigenbaum constants to historical noise. Humans are pattern-matching machines; not every sequence of events is a fractal.

- System Fatigue: The model assumes the system can reorganize. However, if $\tau_n$ becomes smaller than the system’s relaxation time, the system may not reorganize but simply collapse into high-entropy noise (“burnout”).

- Prediction horizon limitations near critical transitions

8.2 Research Directions

Future work should investigate:

- Quantitative measurement of bifurcation intervals across domains

- Network models of reorganization wave propagation

- Experimental validation in controlled complex systems

- Development of intervention strategies for cascade management

9. Conclusion

This paper proposes that bifurcation cascades and reorganization waves represent fundamental organizational principles of complex systems approaching critical transitions. While the underlying energy mechanics differ across domains, the structural patterns of accelerating transitions and synchronized reorganization suggest universal mathematical constraints.

The Feigenbaum universality framework provides a theoretical foundation for understanding these patterns, while critical slowing down offers a mechanism for bifurcation synchronization across coupled subsystems. Contemporary social, technological, and ecological systems exhibit indicators consistent with approach to system-wide critical transitions.

Further research is needed to quantify these patterns and develop practical frameworks for managing complex system transitions. The implications for anticipating and navigating major social transformations are profound, suggesting that mathematical principles from chaos theory may provide essential tools for understanding our rapidly changing world.

References

-

Feigenbaum, M. J. (1978). Quantitative universality for a class of nonlinear transformations. Journal of Statistical Physics, 19(1), 25-52.

-

Scheffer, M., et al. (2009). Early-warning signals for critical transitions. Nature, 461(7260), 53-59.

-

Bak, P., Tang, C., & Wiesenfeld, K. (1987). Self-organized criticality: An explanation of the 1/f noise. Physical Review Letters, 59(4), 381-384.

-

Watts, D. J., & Strogatz, S. H. (1998). Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks. Nature, 393(6684), 440-442.

-

Barabási, A. L., & Albert, R. (1999). Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science, 286(5439), 509-512.

-

Dakos, V., et al. (2012). Methods for detecting early warnings of critical transitions in time series illustrated using simulated ecological data. PLoS One, 7(7), e41010.

-

Lenton, T. M., et al. (2019). Climate tipping points—too risky to bet against. Nature, 575(7784), 592-595.

-

Centola, D., & Macy, M. (2007). Complex contagions and the weakness of long ties. American Journal of Sociology, 113(3), 702-734.

-

Helbing, D. (2013). Globally networked risks and how to respond. Nature, 497(7447), 51-59.

-

Gao, J., Barzel, B., & Barabási, A. L. (2016). Universal resilience patterns in complex networks. Nature, 530( 7590), 307-312.